The new year is the time to try something new and in this week’s episode, both our storytellers approach their scientific problems in the most science-y way possible – through trial and error. It’s also how Story Collider is going to approach this year as we make a few small changes to the podcast. We can only hope to be as successful as our storytellers in our experiments. Happy New Year!

Part 1: Computational biologist Francis Windram is determined to figure out how to make spider webs glow in the dark.

Francis Windram is a PhD student at Imperial College London, working on computational approaches to extracting spider web traits. He is also a musician, poet, climber, and ex-chef, and generally spends his time being a little too enthusiastic about the minutia of life. His passion for education and outreach has led him to teach sciencey things both in the UK and USA, and he believes strongly that in sharing knowledge through humour and candid cautionary tales we can learn to treat ourselves with more kindness, love, and respect than we otherwise would.

Part 2: Avian ecologist Emily Williams refuses to be outwitted by a bird.

Emily Williams is a scientist and PhD student at Georgetown University, where she is studying the migration of a common but overlooked bird, the American Robin. Emily is passionate about outreach and the accessibility of science, and is a fierce defender of the small, underestimated, and undervalued. While she is a Florida native, Emily has done her best to dissociate herself from all Florida man tropes foremost by loving cold and dark places that have topography. Before moving to DC she lived the last five years in Alaska, where she worked as an avian ecologist for the National Park Service at Denali National Park and Preserve. When she isn’t dreaming of a winter wonderland, Emily can be found reading, baking, hiking, and finding new donut places to try.

Episode Transcript

Part 1

I'm going to take you back a few years, 2020. There was a kind of tiny, little thing going on, global pandemic. And I was a lowly first‑year PhD student. Yeah. Great.

I am a computational arachnologist. I specifically look at how we can get spider webs to look good. How we can get good imaging off them. How we can make them show up. So, this was my goal. I look to try and make them show up on these bloody images.

I thought, “How hard can this be?”

So, with my nine‑month review coming up where they can say, “Oh, yes, go for it,” or, “No. No more. Leave. Never come back,” that's all coming up.

So, I decided I'm going to start out looking at using corn flour to sprinkle on the webs, make them show up really nicely on these images, reflect the light. But wouldn't it be nice if the corn flour was like not white? Was like a different color that would contrast.

I mean, you could make it. Sure, you could make it orange. That contrasts brilliantly with green but terrible on brickwork. So, I don't know which color to use.

Francis Windram shares his story at Aces and Eights Saloon Bar in London, UK in November, 2022. Photo by Richard Mukuze.

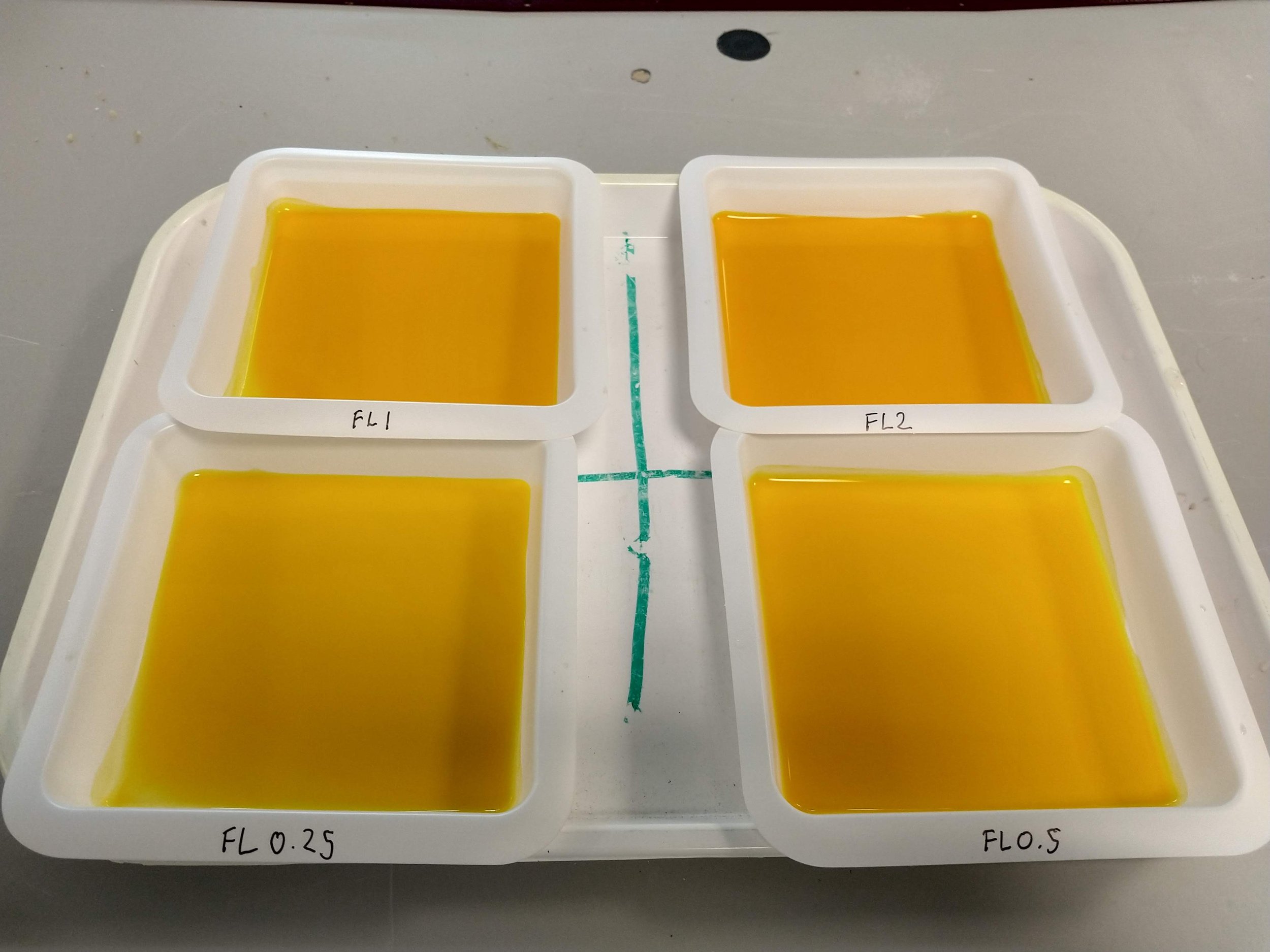

I go ahead and I buy a big old box of food coloring and I go into the lab. I also buy a lot of corn flour. I go into lab with this corn flour. I dilute it down with water, kind of make that sort of suspension you tend to get. Then, I add the coloring. Mix it all together. Mix it a bit more. Put it into these trays and put them into these massive leaf‑drying ovens that we have on the campus.

So I trundle over there with my trays of this what something that looks approximately like Ambrosia custard and I put it in, heaving open these six‑foot doors, chucking them in. And then I have to come back every two hours or so and just make sure nothing has burned.

So I go in and I break them all up. Then, when they're finally dry a few hours later, I come back to the lab, get a pestle and mortar, grind them up then I package them up. Good to go. Head back home feeling pretty satisfied with myself. I'm a scientist, now. I'm a real scientist, I’ve been in the lab. What could be more science than wearing a lab coat, putting on your safety goggles for the dangerous corn flour and going in? I’m doing it. I’m a real scientist.

But I’ve got to deal with I’ve got a lot of colors here. I’ve got to do quite a few of these. I go in the lab the next day, getting more of my colors for the day. Put them out. Make up this corn flour slurry. Mix it up. Add the color. Mix it up again. Put it in the trays. Put it in the leaf‑drying ovens. Come back every two hours and I break it up. I crush it up. Go home feeling a little sore but feeling good. It’s taking a bit of time. That’s fine.

Second week rolls around. This is actually taking quite a while. Like the water turns out it's kind of hard to evaporate. Who knew?

Francis Windram shares his story at Aces and Eights Saloon Bar in London, UK in November, 2022. Photo by Richard Mukuze.

So I start thinking, “Well, Francis, you're a scientist, right? You're a genius scientist. You're coming in here. You're doing all your science things. Maybe you can rub together the two remaining brain cells and make fire?”Ethanol, that's it! Yes. Yes. It's everywhere in this lab, this well maintained and entirely unsupervised lab. There's countless of it. It's there for sterilizing things, all things like that. There's loads of it. No one was going to miss it and it'll evaporate quicker.

But it might affect the color and I don't know if it's going to change the texture or not. I better test this again.

So I get around to doing it. Same process but, this time, with ethanol. Mix it up. Add the color. Mix it up again. Put it in the drying rack. Check it. Stir it. Check it. Stir it. Check it. Stir it. It's dry!

I grind it up. I put it back. But, you see, this time, whenever I check that leaf oven, I open it up and get a blast of ethanol vapor in my face, so it's more like I check it, I stir it, I slightly pissedly check it. I slightly pissedly stir it. I kind of quite drunkenly check it. I quite drunkenly slur it. I cool it. I grind it up sloppily and then I stumble my way home.

Week three rolls around. Turns out, ethanol is actually no better than water. I had wasted that time. But, no. It's fine. No. No worries. Don't worry about it. It's just keep on moving on.

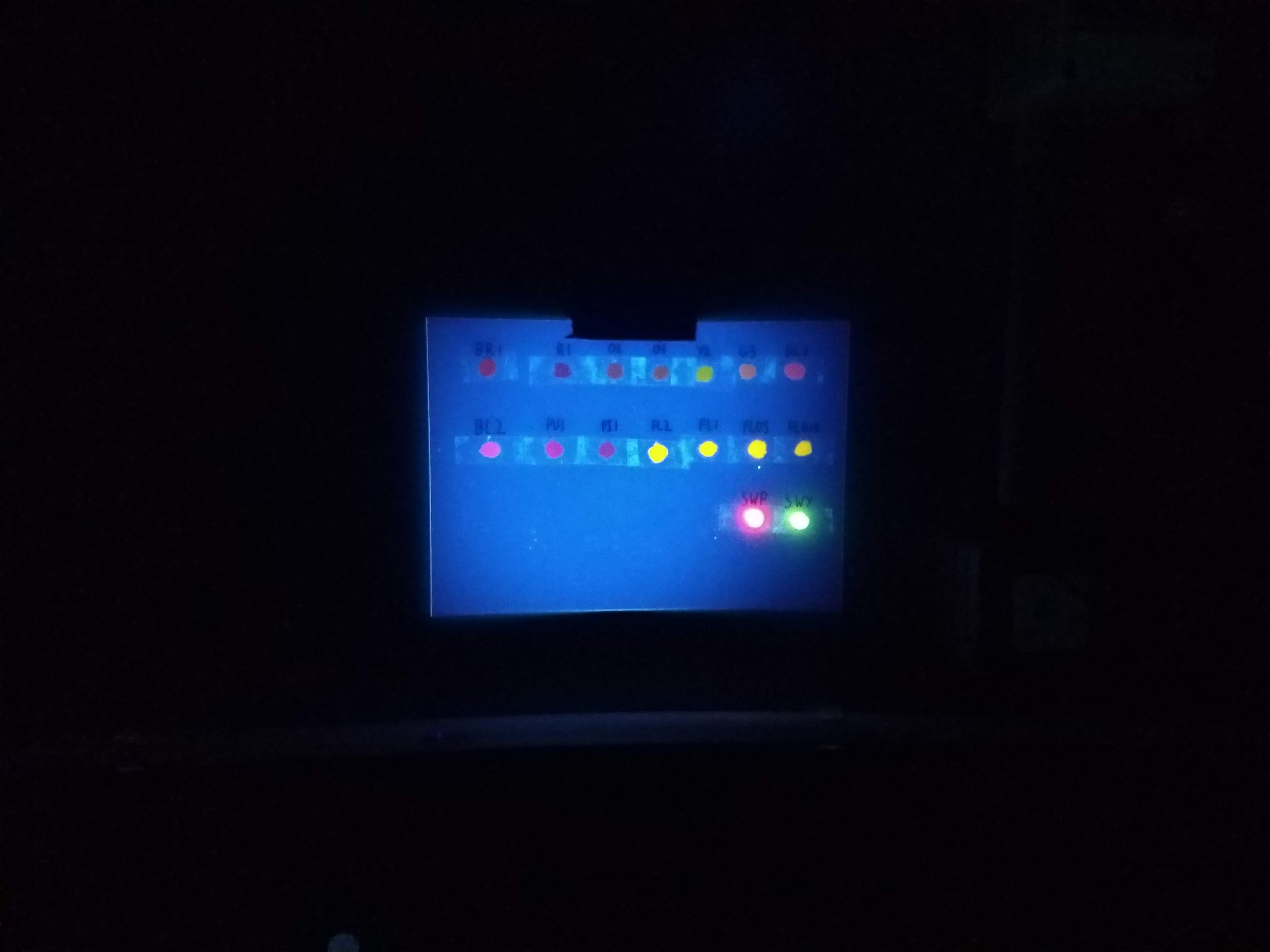

But what about that whole making it show up at night? So I could use UV to do that but I’d need something that was UV fluorescent. Well, come on, Francis. Genius fucking scientist, right? Let's have a think.

That's it! Riboflavin, Vitamin B12. It's fluorescent. It's pretty easy to get. I'm pretty sure I saw it just in the lab supplies. It's a bit expensive but it's fine. It's already there. But I don't know how much I need to get it to actually show up and to glow under UV. Shit, I better test it, don’t I?

So, back in the lab, week three, all my colors again. I've got the process down but like it still takes a lot of time. Add different measurements of riboflavin. Mix it. Add the color. Mix it. Take it to the leaf‑drying ovens. Open them up. Shove it in. Close it. Open it. Check it. Stir it. Check it. Stir it. Check it. Stir it. Bring it out. Grind it. At this point, it's kind of starting to take the piss.

Fourth fucking week rolls round but, by the end of that fourth week, Friday 8:00 PM I've done it. I'm there. I'm so happy.

I go outside to check it with this UV torch and go, “Yep. Yep, that's glowing. Brilliant. You've done it. You've actually done it. You're an actual fucking scientist.”

I pack everything away and I saunter home. And I think, “You know what, Francis, you've done a lot. You've done a lot here. You've really— this is an existential dread moment. There's this whole pandemic going on. Everyone's stressed. You've done it. You know what you deserve? I think you deserve a takeaway.”

So, I go and I get myself a lovely curry. And to go along with this lovely curry, I get myself a gin and tonic, because what pairs better with a curry than a gin and tonic?

I sit down to eat this lovely Ceylon curry from the local curry house and I notice the oil on the top. It’s kind of yellow. It's actually, hmm. It looks a little bit like the professional pigments I was looking at before.

So I pick up my curry, I pick up my strong drink, I pick up my UV torch and I head outside into the pitch black. I turn on my torch.

Fuck! Fucking fuck! There, glowing bright fucking yellow is my celebratory fucking curry. I cannot believe this. I am crestfallen, frankly. I put weeks and weeks of effort in. I felt naïve. I felt like a little child.

How am I going to get this past my supervisor? What? I spent four weeks in the lab discovering that turmeric exists? I'd gone down a rabbit hole. Unfortunately for me, there was this fox called an appropriate amount of turmeric waiting at the edge.

All right. At least I can enjoy this curry, right?

So, I turn around, curry in hand and the UV torch is still on. As it passes over my gin and tonic, it's also glowing bright fucking blue.

Francis Windram shares his story at Aces and Eights Saloon Bar in London, UK in November, 2022. Photo by Richard Mukuze.

What can you do, man? Like I sit down on this cold step. How am I going to make it as a scientist if I can't get these basics right? What the fuck am I trying to do? Really? My entire plan was entirely one-upped by a local curry house and fucking Schweppes?

I go back inside. I sit down with my fucking curry. I enjoy it. It's a very good curry, okay. And I still enjoy curry and I still enjoy gin and tonic.

But I look back at this now, few years later. A bit of hindsight. I'm like, “Did I really fuck up that bad? Like, really, when you actually look at it, I got super invested in it. I had my blinkers on. I wasn't thinking about this. I was just doing things.

Imagine if after the first week, after that first celebratory bit I went and got my celebratory curry then. Then maybe this wouldn't have happened. In not taking the time to appreciate the small wins, I hoisted myself by my own petard.

So, yeah, in the end I can still drink curry. I'm still on my PhD. It's looking good. This wasn't the end of the world. But, right at that moment, it fucking felt like it. But we're here now.

Thank you very much.

Part 2

In almost all things, I have gone through life with the attitude that if there's a will, there's a way. And that's how I was facing the second field season of my PhD.

The odds were stacked against me in a lot of ways. As I was approaching year two of data collection, I had had a meeting with my PhD advisor. He tells me, “You got to get ten recaps.”

Emily Williams shares her story at Smitty's Bar in November 2022 in Washington, DC. Photo by Lisa Helfert.

I was thinking this is pretty ambitious, but I wasn't going to tell him that. What I mean by recaps is that I have to recapture the same bird that I captured the year before. And what capture means is exactly that. I put up big net scenarios that I think my study species, the American robin, a small migratory songbird that a lot of people associate with as the first sign of spring, is likely to fly through.

If a robin flies into one of my nets, I safely extract it out and I take a bunch of measurements. But then I do the most important part. I put a GPS tracker on it.

The thing about these GPS tags, though, is that the data gets stored on the tag itself. So the tag doesn't remotely transmit to some computer far away. It means that I have to capture that bird, take the tag off, take the tag home, plug it into my computer much like a USB and download the data. So every single tag matters.

The reason why I'm putting GPS tags on robins is because the main question of my PhD is that I want to study their migration patterns. So when and if they migrate, how far do they go, where do they go and what influences those decisions.

Emily Williams shares her story at Smitty's Bar in November 2022 in Washington, DC. Photo by Lisa Helfert.

One would think we’d know the answers to this already, especially given how common the robin is, but the fact of the matter is we don't. And answers to those questions are critical for understanding how birds like robins and other animals will cope with environmental change like warming climate.

It's early spring. I'm in the first week of my field season and I've got my sights set on a particular robin that I put one of these GPS tags on. I'm in the front yard of the house in which I captured this bird last year and I don't see him. Damn! Did he survive? Did he come back?

I go up and down the street several times and I finally spot him. I see him on the ground looking for worms in between two houses that I don't have permission for. Shit.

So I kind of like look around and then I see somebody in the backyard that looks like they're gardening. This must be one of the homeowners.

I cold‑walk up to the guy and I give him my spiel. “Hi, I'm Emily Williams. I'm a PhD student studying American robins. Can I come into your yard at 4:00 in the morning to catch a bird?”

Let me just say bless all the people who graciously let me work in their yards because I realize how ridiculous that sounds.

The guy at the house on the left is a yes, so now I got to get permission from the house on the right.

Emily Williams shares her story at Smitty's Bar in November 2022 in Washington, DC. Photo by Lisa Helfert.

I eventually catch up with the homeowner in a subsequent visit to the neighborhood and she's a little more skeptical.

“You're doing what to the birds? How is this helping them?”

After a more lengthy conversation about my research and why it matters, finally get the green light. Bomb. All right. Time to catch our guy.

On the fateful morning, my field tech and I arrive on the scene at 4:00 and we get set up. We set up this verifiable booby trap of nets in the backyard, in the side yards, in the front yard and then my tech and I go find an inconspicuous spot to hide where we can get good eyes of our nets but also we can look for our bird. It's still pretty low‑light conditions but I'm pretty sure I see them up high in a tree.

The reason why we started at such ungodly hours is the fact that robins are awake at this time. You know that bird that goes, “Cheerio, cheerly, cheerio,” outside your window at 4:00 in the morning? That's them.

So they're awake but they're usually hanging out high and the goal is that we set up these nets when robins can't see very well and that, by the time they're starting to fly lower, they'll get caught in the nets. But if robins see a net, it's game over.

The thing that I haven't mentioned that makes catching robins a formidable task is they are smart. They are ridiculously smart. So smart that they recognize human faces. And they remember.

You know that saying, “Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me”? Robins came up with that.

So we're waiting for the light to break. We're waiting for our robin to do something and it starts to rain. I swear I had checked the forecast that morning but, as per usual, the meteorologists were wrong. The rain that was forecasted to come hours later started right then, right now, in a fucking downpour.

Of course you don't want to net birds in these conditions because they can get wet and they can get cold and that can be stressful and you don't want that to happen, so my tech and I run out and we quickly close the nets.

Guess what happens? Like the ever‑seeing eye of Sauron, our bird watches our every move. It imprints it upon his memory.

The rain of course lasted for hours so we blew our chance. The score was set. Robin one, Emily zero.

I try the next week. Robin two, Emily zero.

And I try again, and again. And each time I try, I bring out my whole arsenal of tricks and each time I visit I have to be even more creative. I found his mate. I captured and banded her. I found her nest. I followed them around and I figured out where all their favorite spots to hang out were. I figured out where they like to eat and I put nuts in all of those locations, and the birds were nowhere to be found.

The score is increasingly getting higher in the robin's favor and I feel like I'm actually getting in the negative.

This one time, I thought, “Well, maybe if I disguise myself, that would fool the robin.”

So I buy masquerade masks for me and my tech and we wear those. And then we put COVID masks on and we think if our faces are completely obscured the robin won't recognize us. Again, I failed and the robin won. The score is robin seven, Emily zero.

By this point, we come from April to July and time was running out. I had gotten nine other robin recaps that season and I was so close to my goal of ten recaps. I was not giving up on this bird. This robin held on its back the key to the wonders of robin migration. How could I miss out on that?

We're at the end of July and I decided to try one last time, except this time I have convinced ornithologist friends to do the work for me because, by visit four or five, the robin would literally evacuate the area as soon as I showed up. I swear this bird even recognized my car.

Emily Williams shares her story at Smitty's Bar in November 2022 in Washington, DC. Photo by Lisa Helfert.

So this time I actually show up in a different car. I stay in the car and my ornithologist friends are the ones to check the nets. And after several hours of trying, we catch a lot of other robins but not ‘the’ robin. We didn't get him.

I had put so much hope and so much willpower and so much effort into catching this bird and no matter how hard I tried, I just couldn't get him. I didn't want to face the fact that I had failed. The disappointment was raw and I didn't want to face my PhD advisor and tell him that I not only failed in not catching this robin but also in not getting ten recaps for the season.

I really hate to be admitting this but I got outwitted by a robin. This Wile E. Coyote of a robin taught me that when sometimes there's a will, there's not a way. And sometimes things don't go as you have them planned and you just got to let that go. In this case, quite literally.

Even though this robin will be forever burned in my soul as the one that got away, I keep a flame of hope that he'll be back next year.