July is Disability Pride month, which is all about empowerment and visibility for those with disabilities. In honor of Disability Pride month, this week’s episode features two stories from the point of view of people with disabilities.

Part 1: When Julie Baker is diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and told her vision might get worse, she struggles to accept she’s going blind.

Julie Baker is a Boston-based writer and producer. After competing in and winning her first Story Slam in 2017, she quickly became a storytelling addict and evangelist. She’s performed on PBS Stories From the Stage, The Moth, Now Listen Here, YouTube (@bluechakrastories), Instagram (@lazyjulie), and anywhere else where people will let her tell stories. She considers it her mission to expand the storytelling community and spread the word about how true, personal stories can change the teller and the world.

Part 2: Javier Torres becomes frustrated with others' responses to his neurosensorial hearing loss.

Javier Torres is a jack of all trades from Puerto Rico, figuring it all out, one day at a time. Learning about what it means to express himself through improv, comedy, creative outlets and DIY sewing projects.

Episode Transcript

Part 1

It's a sunny fall day, so I decide we'll walk to the store. Eight year old Ruby is on my right. Four year old Zane is on my left. Ruby thinks she's way too big to hold hands but she knows the rules. When we cross the street, we hold hands and we stay in the crosswalk.

Zane's a lot less reliable. He's been known to just take off and chase a dog or a leaf or something, so I'm holding him a little bit harder.

I hear the car before I see it. The screech of the brakes and this shiny, white, fancy car is parked, like stopped like a foot away from us in the crosswalk, 12 inches away from me and my kids. It takes me a while for my heart to slow down but Ruby's just babbling on like nothing happened. She's talking about the latest episode of Kim Possible and Ron Stoppable and his pet, but I'm still thinking about it.

Julie Baker shares her story at Turtle Swamp Brewing in Boston, MA in March 2023. Photo by Kate Flock.

I realize nothing happened but something might have happened. And that if I was driving that shiny white car, that I probably couldn't afford, I don't know that I would have seen those people in the crosswalk. I don't know if my vision would have been good enough.

When I woke up blind in one eye and I had like a lot of tests and a lot of specialists and I was diagnosed, ultimately, with multiple sclerosis, the neuro ophthalmologist told me that my optic nerve issues meant that my vision was unpredictable and it might get worse. And it has gotten worse. My depth perception is shot. I'm starting to bump into other cars, but they're just fender benders. It's not that big of a deal. And I stopped driving at night and I stopped driving in the rain. And if I didn't sleep very well and I'm kind of tired, I know my vision's wonky so I stopped driving then.

But when this car screeches to a stop, I think, “Okay, on a sunny day, when I slept really well, would I have seen this family?” And I couldn't say yes definitively.

So that was it. I put my keys in the drawer, I parked my $1500 Craigslist Volvo wagon that had all the best bumper stickers on it. I parked it in the driveway and I closed the curtains, because it made me sad to look at it outside.

But I'm a single mom and single moms do not have time for sad. We figure stuff out. So I walk the kids to school. On bad weather days, I have neighbors who drive them to school. I ask my boss if I can work from home three days a week. I get a T pass. I figure it out and I keep figuring it out.

I make friends with the other soccer parents and the swim club parents, even the ones I don't like, so my kids can get to the meets and the games. And I figure it out. I end up having a 5.0 Uber and Lyft rating because I'm figuring it out.

And then my kids graduate from high school one at a time and they're off to college. And I don't need this big apartment in a burb where they get a really good education. I want to live in the city. I'm a walker. I'm a pedestrian. I'm a T rider. I don't need to be there anymore.

So, I look at an apartment in the city. The only one I can afford is in a neighborhood far away. I am having trouble because I don't know all my routes by heart anymore, but I'm going to figure it out.

If I go out the wrong exit of the train station, yeah, I get lost, which is really quite an accomplishment when you live in East Boston because it's a very small neighborhood. But I tell myself it's fine. I'm just acclimating to my new community and I needed the steps anyway.

Julie Baker shares her story at Turtle Swamp Brewing in Boston, MA in March 2023. Photo by Kate Flock.

Then I realize it's even hard in my building. I live on the third floor and there's gray steps. I can't really tell where one ends and another begins and I fall down the stairs. And I'm carrying the recycling, so it's a really dramatic fall. There are cans and milk cartons and the neighbors come out because it's really loud.

I convince them I am fine, I am fine, I am fine, and I convince myself I'm fine. And then I get reflective tape. I thought, okay, I figured it out again. I get reflective tape. I put it on all the steps. I figured this out.

The next time I go to the neuro ophthalmologist, he tells me that I've crossed over into legal blindness. I make a joke and I say, “You'd think there'd be like a warning sign or a bail or something when you cross that line,” and he laughed. Then he told me that he was going to refer me to the Massachusetts Commission for the Blind and I did not laugh. I was horrified.

I said, “Are you really allowed to do that without my consent?” He thought I was joking. I wasn't.

The Mass. Commission for the Blind calls me and they do this intake interview. I try to set them straight right away. I said, “Listen, I am not blind blind. I'm sure your budget and your services could be better used to help someone who really needs it.” He just listens.

Ultimately, I'm referred to the Carroll Center for the Blind and I'm told that I'm going to get a coach. I thought, “Seriously? Like is blindness a sport? Does it require a coach?”

I don't want one but she shows up. She does a whole interview process, checking out what I can see, what I can't see, asking me questions. At the end of the session, she starts talking about blind cane training.

I said, “Whoa, whoa, whoa. I am not doing blind cane training. I am not blind blind. I can still see you. I can see you sitting where you're sitting. I am not that kind of blind.”

She said, “Okay. Well, what is your issue?”

I said, “Well, I don't want to be a victim. I don't want to signal to people that I'm vulnerable with the blind cane, because, you know, bad things could happen to me.”

She said, “Okay. Didn't you tell me you fell down the stairs?”

I said, “Yeah, but, you know, it wasn't that big of a deal.”

She said, “Didn't you tell me that you have to look at your feet on the street to make sure you don't trip and fall?”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah.”

“Didn't you tell me you mistakenly walked into the men's locker room at the Y?”

“Uh huh.”

“Well, do you think those things make you vulnerable?”

And I just thought, “Okay, whatever. But I'm still not doing it.”

The next visit, she brings the cane and suggests I put it in the corner and just get used to it there. We go out for a walk, her, she has the cane. I don't have the cane, but it's still really embarrassing because everybody's looking at her. I'm sure they are. I can't really see them but I'm pretty sure they're looking at her. And I know by association they're looking at me.

When I tell her this, she does not tell me I'm a self centered asshole. She tells me that, in her experience, people are usually thinking about themselves and not about me.

Then I fall on the street. It's daytime. I'm walking. I think I know where I'm going. There's people around. I trip and I fall and I'm bleeding. There are people there so I'm embarrassed and it hurts.

So, I call her and I say, “Okay, I'm ready. I think I need to do the cane training.”

We start training with the cane. It's much harder than it looks. Stairs, I'm still really sucky at, but we go on the train. We do all kinds of things, but I'm still embarrassed and I keep it folded in my purse. I only use it when I absolutely need it.

When we were on the train, I told her that I'm pretty sure people think I'm faking it, because I don't look blind and I'm looking at my phone.

She laughs again and says, “Do you think blindness is all black or all white? Blindness is a spectrum.”

On one of her visits, she asked me about grocery shopping. I said, “No problem. The Shaw’s is a half a mile away. I know how to get there. I go in the daytime. I know where everything is in the store. Or I order on Instacart.”

“What happens if you need something in a hurry and you can't find it?”

“Well, I do without.”

She suggests we walk to the grocery store together and she might be able to help me.

We go to the grocery store. We stop in the little vestibule with the red box and she tells me that she's not going to go grocery shopping with me and asked me did I get the list. Did I make the list on my phone like she instructed? Did I include things that are difficult for me to find? Yes, yes, yes. I did all of those things.

She tells me about an app that'll look up at the aisle and tell you what's in that aisle, another app that'll make things big so you can read ingredients. I don't need any of that.

I find everything I need, except for two items I can never find: light coconut milk in a can and a spice mix that has garlic and sea salt and peppercorns. Those are the things. Sure enough, I can't find them. I think it's going to be in Latin American, the coconut milk. It's not. The spice aisle, it's like a shit show. There's just too much going on visually.

So, she explains I should go up to the service desk. It's called customer service because I'm a customer and I need service. And then I should keep the cane visible. I don't have to use it in the store but I should keep it visible.

So, I go up to the counter and I'm like, “Yes, I'm visually impaired and I can't find these two things. Do you think you can help me?”

She says, “Sure.”

I'm ready with the cane, because I know that sometimes people try to take your carrot or take your list on the phone and I've decided that if she tries to do either of these things, I'm bopping her in the head with the cane. But she doesn't try to do these things. She helps me find it. Apparently, like coconut milk is in with the Indian food. I find an even better sea salt peppercorn garlic mix. It's taller. It's much better and I'm excited.

Julie Baker shares her story at Turtle Swamp Brewing in Boston, MA in March 2023. Photo by Kate Flock.

We had made arrangements that she was going to leave me alone and I was going to meet her on the other side of the registers and I'm really feeling myself, because I've gotten everything on my list and I even asked for help.

I go through the register and there she is. And I tell her, “I got everything on the list. I asked for help.”

I looked down and she's got a Shaw's bag and I realized she was doing her own shopping. She was not stalking me in the paper towel aisle, like I thought she was.

I was feeling so proud of myself that I just walked home all on my own. And I start noticing, you know, this cane isn't half bad. I can look up, I can walk faster, I can feel bumps in the sidewalk. It's incredible.

Now, I'm using the cane all the time. I used it in an airport, which, you know, that was a whole thing. They tried to offer me a wheelchair and I said, “Um, no. Problem with vision not problem walking.”

I used it on a date. I didn't die. I didn't die.

I want to use it. I want people to see this is what blind looks like. This is what blind looks like and it's not awful.

When I first talked about using the cane with my coach, she suggested I call another reluctant cane user named Holly. I called Holly and Holly told me everything changed when she named her cane. And that she named her cane ‘Stanley’.

I said, “Yeah, Holly, that's really cute and all, but if I were to name my cane at this point, his name would be ‘Fucking Dickhead’.” So I'm definitely not ready to name the cane.

But, lately, when I step outside and I snap it open and I feel like it's a Luke Skywalker Jedi lightsaber, I'm thinking, “I'm ready.”

I'm still deciding, but I'm going to text Holly and maybe have her vote because I'm back and forth between Stella and Michael Cane.

Thank you.

Part 2

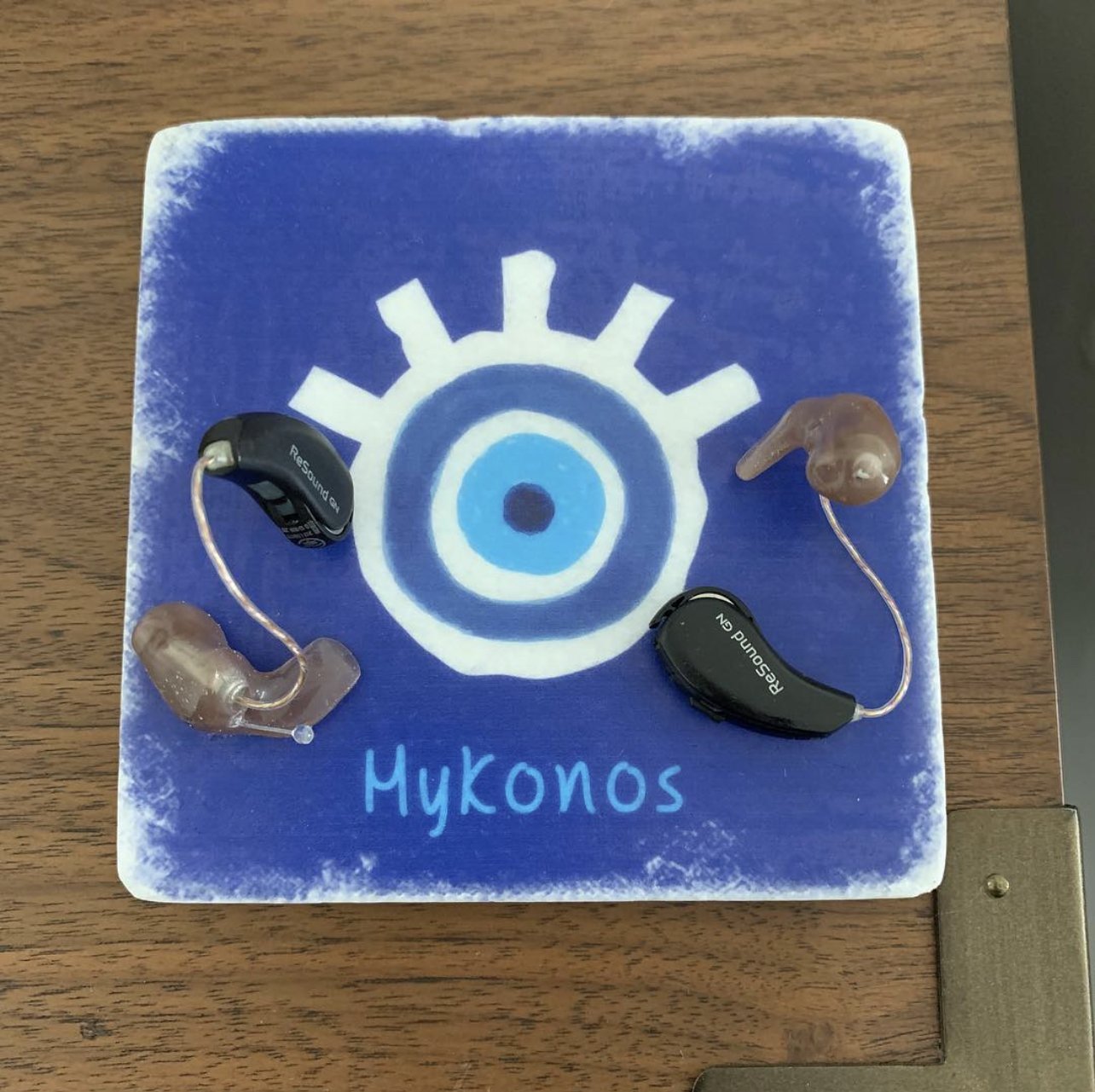

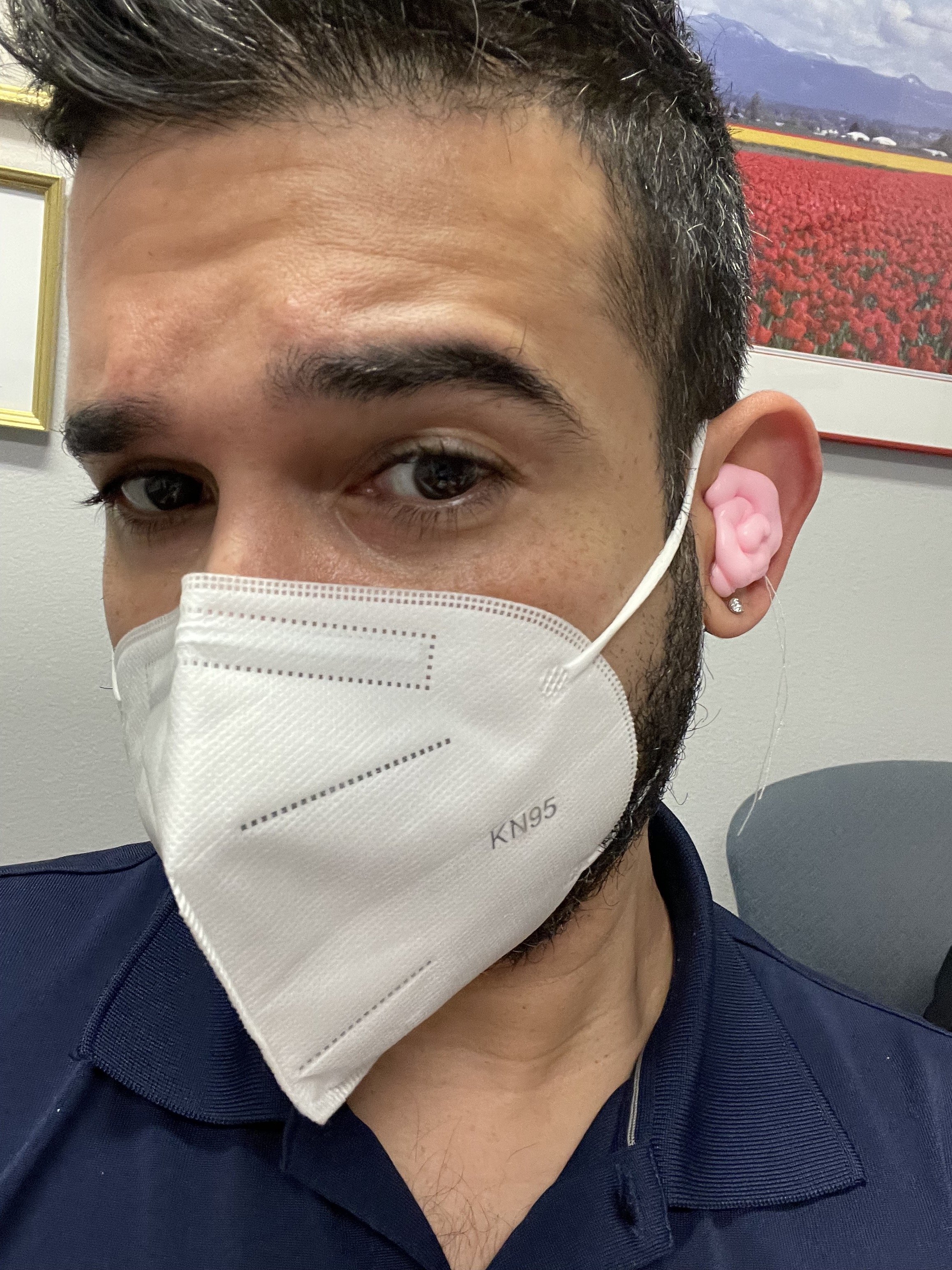

I was born with a neurosensorial hearing loss, which means that the nerves in my ears that are responsible for carrying sound to my brain don't work properly. This accounts for 75% of my deafness.

Now, I didn't use hearing aids until the age of three, so you can imagine what kind of happy baby I was until science intervened and brought me into the hearing world.

It's crazy how people without disabilities have so much to say without realizing the psychological impact that they can have on a person. I forget that I'm deaf until the world reminds me.

Like I'm entering this restaurant that used to be a former church and, as I open the front door, I greet the hostess saying, “A table for two, please.”

I'm getting ready to meet someone on a first date. I'm super nervous. The host was taking me to my table, I sit down wondering and clearing my throat to make sure that my hearing aids are working, that the batteries are working properly.

The waiter comes by, drops off a basket of four pieces of bread. I think two for me, two for my date.

I take a moment to recalibrate my hearing aids again. I adjust the volume because I was not going to miss a beat of this engaging conversation I would inevitably have with this person.

Javier Torres shares his story at the Jewelbox Theater in Seattle, WA in May 2023. Photo by Elizar Mercado.

20 minutes go by and I'm now down to one piece of bread in that basket. I've depleted my allotment of bread and, well, my date does not need to know that, I think.

Then, suddenly, I hear the bell on the front door of the restaurant open and I see my date walk through. As he walks slowly towards me, I start to clear my throat again to double check my hearing aid volume. I can hear myself fine.

I get up to say hello to him. He's towering over me almost by a foot as his hair dances in the wind of the air conditioner.

I sit down and I start to get anxious and nervous and I grab the last piece of bread from that basket. I wonder how long it'll take for him to notice that I'm deaf, that I wear hearing aids. Not a moment goes by that he clicks to my side and smiles and gasps, “Oh, my God. You’re deaf? I love deaf people. They're like whales in bed.”

I am shocked. I choke on the piece of bread that I have stolen from my date. I quickly go for a glass of water to down the choking to save myself from elimination and I decided that, you know, this was not going to be the happy ending I thought it was going to be and I execute my evacuation procedures.

I tell him that I have planned to meet friends at a bar for drinks so I leave faster before he has a chance to say, “When can I see you again?” Never, I think.

As I get out of the restaurant, the Uber that I had summoned arrive. I open the front door and I hear, for security purposes, my name to be confirmed, Javier. I say yes, because I just want to get out of there and meet my friends and tell them about this amazing date that I just had.

As I get into the car, I click my belt and the car takes off. I suddenly feel like I'm inside of a tornado. It was a very hot and summer day, so all the windows of that car were open. So all the wind is blowing against the microphone of my hearing aid so all I hear is just like “shh” the entire time.

I look in the rearview mirror of the Uber and notice that the person's looking at me moving their head. I know they're talking to me. I can't hear anything. I just smile and nod, hoping I'll survive this car ride.

I start to feel guilty. I start to feel like I'm being fake. What if they're telling me a sob story and I'm just there smiling and nodding to his sad story.

I noticed I'm only a block away. The awkward discomfort would only last 30 more seconds. Finally, the car stops. I get out and I hear the Uber say, “Have a great day,” to which I reply, “You too.”

Thank goodness it wasn't a sad story. I didn't offend the Uber driver. And I start to think that that's one of the reasons why my Uber rating will never be perfect.

As I exit the car, I go meet my friends at the bar. I see two of them there having drinks. As I get closer, I notice there's a third person there I've never met before. I think to myself, “This time, I'll get in front of it. I'll tell them that I'm deaf so it won't be awkward.”

So I say hello to them and I say, “Hey, my name is Javier. And just so you know, I'm deaf. So if I ask you to repeat yourself, it's because, you know, I'm not ignoring you. I just need your help to understand.”

They reply back to me, “Oh, I know. You didn't have to tell me. I could tell by your voice.”

Javier Torres shares his story at the Jewelbox Theater in Seattle, WA in May 2023. Photo by Elizar Mercado.

“My voice?” I didn't even know that was a thing. Like, add that to my list of insecurities of why I'll never be like anybody else.

And I'm like, “The moment I open my mouth, people can tell that I'm deaf?” That just feels so uncomfortable, so wrong.

I begin to hate myself for not standing up for myself and telling that person like how dare you say that. I just swallow those feelings and finish the rest of my vodka club soda with a splash of Cran.

I finish the drink. I start to feel chilly as it becomes closer to night time. I remember that I actually had plans to see a movie at a friend's house. So I get up to leave and I say goodbye to my two friends and the third individual whose name will be forever masked in obscurity.

I leave and I arrive closer to my friend's house for the movie. As I go through his front door, I can hear the cackling and excitement of a lot of people inside and I start to smell freshly baked cookies. Ah, a comforting smell, I think.

As I get closer to the area where the cookies are, I see the host and I quickly went up to him. “Hey, it's a little bit loud in here. Do you think we can put on the closed captioning,” I ask. He quickly puts on the closed captioning on the movie.

I take my spot next to the coffee table where, conveniently enough, the cookies were placed as well. I grab a cookie and not a moment right after the opening sequence of the movie, I hear right behind me, “Oh, my God, why is there closed captioning on? I can't even focus on the movie. It's so distracting.”

Mortified, I look for the host and I give him the signal to just take it off. It doesn't matter. I can totally understand what's going on. It's fine. It's fine. I don't want any more unwanted attention. I don't want anyone to ask me any questions. I only knew the host. I didn't know anyone else.

So, resigned to suffer in silence, I grabbed the cookie that I had and slinked to the back of the room. I get on my phone because I can no longer follow along with the movie.

Moments later, someone comes to me and says, “Oh, why aren't you watching the movie?” At that point I am just tired. I'm exhausted and frustrated and I respond back, “I'm deaf and, honestly, I don't have any more energy to pretend that I'm enjoying the movie. I just don't care.”

And the person looks at me with their deep piercing blue eyes and I feel bad now that I made that person feel bad that I felt bad. It's my fault for creating that awkward situation. If I didn't ask for the closed captioning, none of this would have happened.

I start to resent myself for not standing up for myself but also putting myself in those awkward situations. Why am I doing this to myself?

I don't even notice how the pandemic starts to change the world around me. Everyone is now working remotely with their cameras off. In physical world, people are wearing masks so I can't read their lips anymore.

I start to get even more tired being on just trying to be a part of the conversation. I decided it's not really worth it. Is it really worth it to be part of these conversations? I start to hate myself for thinking that. I waste so much energy. I'm so exhausted. I think I decided to go to therapy.

Javier Torres shares his story at the Jewelbox Theater in Seattle, WA in May 2023. Photo by Elizar Mercado.

After a year of therapy, 4:30 every Monday, I would prop up my laptop camera and take on my video therapy sessions, until one day the therapist tells me in regard to the social situations I've been in, “What is it that you're afraid of? What's so bad about them?”

As I struggled to formulate a response, tears begin to stream down my face and I realized the reason why they're so difficult for me is I feel like I have to be on because, otherwise, I'll be left behind. I'll be viewed as weak, incapable, always an inconvenience to others because I have to be accommodated. And I hated that. I hated myself.

As I said those words, a huge weight lifted itself on my shoulders. I started to realize that I was living my life afraid. Afraid of what would happen to me if I didn't overcome my disability. I started to realize that the only person that needed to love me or accept me was myself.

I begin to create new experiences for myself and live life on my own terms. I joined an improv musical troupe, which was one of the scariest things I would do. I began to go back into improv with new and old friends alike and I no longer have that anxiety and that fear. The moment I started to move forward, the path materialized when I started to live my life through my own terms and not through the lens of how others might perceive me.

Thank you.