I’m in my sophomore year science classroom, reaching a latex-gloved hand into a tank of underwater frogs. Contact: my fingers meet slimy skin. With finesse—as much as a sixteen-year-old can muster—I grasp the frog’s body, my fingertips on his belly. I flip him over, and his little limbs go wild, but I manage to slip the needle beneath the skin on the underside of one of his legs. In goes the sex hormone.

* * *

I liked science, it was true, but I really liked being deemed a “gifted” student.

This was my first year in my high school’s Science Research Program. Ten of us had been chosen to direct our hyperactive type-A energies into minimally supervised, original research projects. I’d been gunning for selection and was ecstatic—or relieved?—to be part of this group. I liked science, it was true, but I really liked being deemed a “gifted” student.

After thoughtfully highlighting dozens of articles from Science, wishing I had glasses to make the studious scientist image complete, I’d settled on a plan. I would study the mating calls of Xenopus laevis, a species of frog native to South Africa.

I wasn’t quite passionate about frogs, but the project sounded impressive. Impressive enough to win a science competition, maybe? At the end of the year, we’d line up our poster boards in various classrooms and auditoriums, reciting the implications of our heavy-duty research wearing slacks, maybe even skirt suits. I wanted, of course, to place.

My research goal was to figure out whether males’ calls changed as competition increased. I’d keep the number of females constant at one, changing only the number of males who surrounded her. A sleek, easily controlled experiment, I thought. And simple enough, right?

Except for a few minor details. Xenopus laevis are underwater frogs, so I set up tank upon tank in our science classroom to house the two females and multiple males I’d garnered for the experiment. Picture those black slab tables that tend to house Bunsen burners, topped instead with a mini-aquarium.

Did other students need to use the classroom for their experiments? This question occurs to me now, rather late.

In the middle of the floor, I blew up a kiddie pool in which to conduct the various trials. (Did other students need to use the classroom for their experiments? This question occurs to me now, rather late.) After some thought, I plopped a laundry basket into the center of the pool to serve as the barrier between males and females. I’d put a female frog, love object extraordinaire, into the basket, and set the males—one, two, or three—loose in the surrounding pool. Foolproof, and totally safe for the frogs, I thought.

But how to record mating calls underwater? For this, too, the brilliant child researcher found a solution. I located a little microphone to plug into my recorder and wrapped it in cellophane to protect it. Insert tape, close cassette, press play, dunk.

The real challenge was how to encourage the males to call in the first place. Xenopus laevis mate in the summer and, as this was a school project, I needed them to want to mate in the winter. Choose an animal with an appropriate breeding season? Why would I do such a thing when I could find hormones with which to inject my research subjects?

So there I found myself, coming to school every weekend to flip slippery, squiggly frogs on their backs and give them a dose of the good stuff. Again, totally, totally great for the frogs.

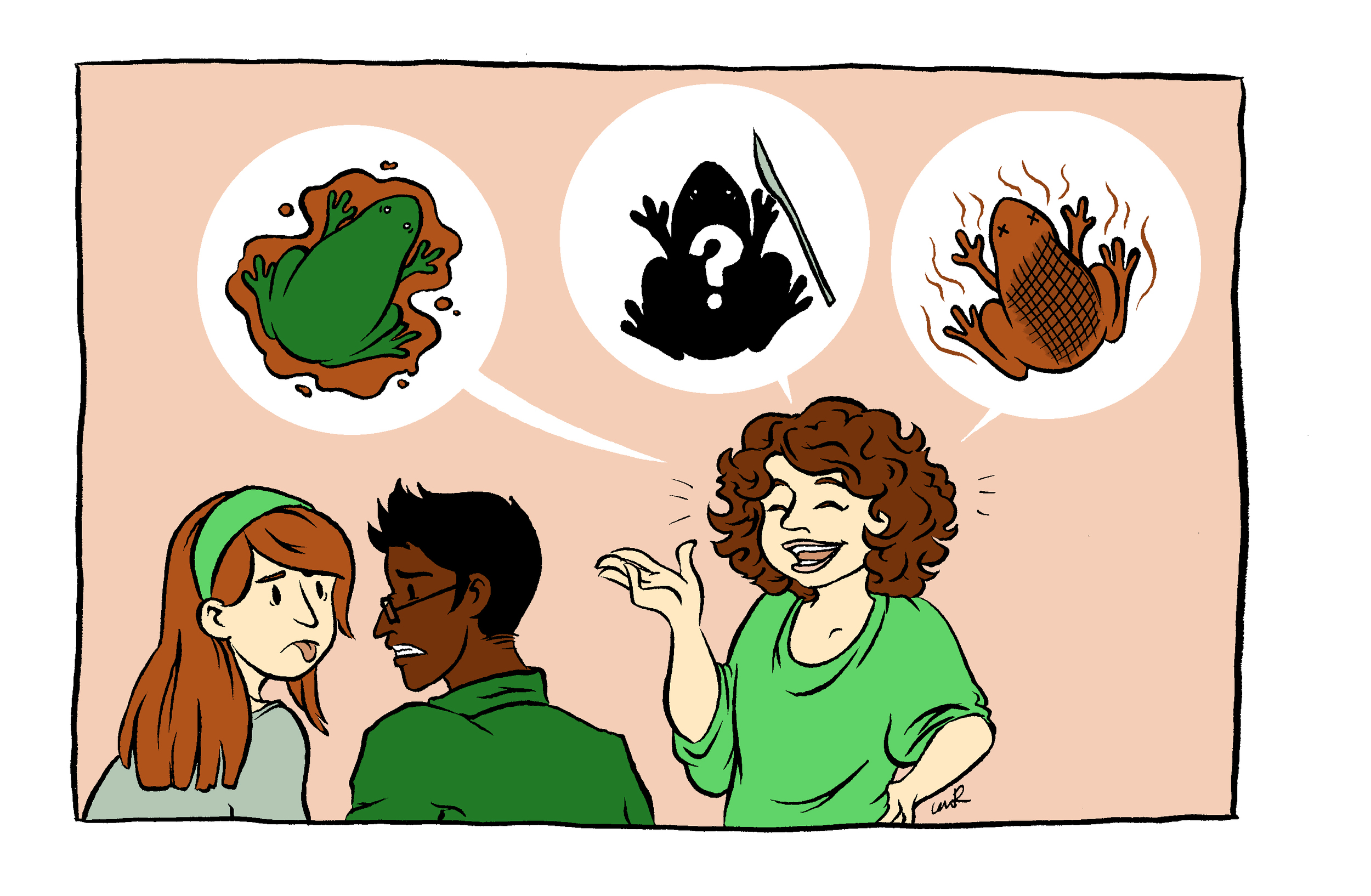

By the end of the year, I’d recorded enough mating calls to feel successful: the males were sufficiently moved to express their primal needs, and my cellophane-covered microphones managed to pick up their calls. I found a computer program that transformed the audio recordings into visual depictions. There each call appeared, a black-and-white Rorschach on my screen. I studied the images, comparing the formations produced by only one male to those recorded when there were two males and three, and—triumph! The mating calls did, in fact, change along with the number of males paddling around the kiddie pool. I did well at the science fairs, I think. I can’t remember too clearly. Kids, see how that works?

What I do remember is that the frogs didn’t fare as well. Bertha, one of the two plump females, had started bleeding from her fingertips during the experiment. I’d transferred her to a green, plastic garbage can, where she could recover apart from the other lady frog, but the water quickly turned muddy, little red rivers coursing from her webbed feet. She perished. Then, while changing the water in one of the males’ tanks, I placed him momentarily in water that was too hot. He had a seizure, because I’d boiled him.

One of the males managed to escape from his tank and, despite a thorough search of the classroom, remained hidden. A couple of weeks later, a classmate located him in a corner of the room, still and hard. My teacher, an eccentric lady who claimed to have played with mercury (the potentially toxic innards of glass thermometers) as a child, was ecstatic. “Oooh, let’s dissect him!” she trilled. “Unless…you’re not ready?” The question struck me as odd: ready for what? An awkward silence later, I realized that, were I a different person—one who’d cared for the animals—I’d feel upset. I consented to the dissection.

* * *

In college, one of my best friends nicknamed me “Frog Girl.”

I was especially fond of the bit about the seizing frog: Wasn’t it hilarious?

It had been several years since the experiment, but my high school frog-saga had become mythic in my mind, and I told the story so many times I forgot who’d heard it already. With each retelling, the focus shifted more and more from the experiment itself to the frogs’ deaths. I was especially fond of the bit about the seizing frog: Wasn’t it hilarious?

Sometimes, my friends laughed. But other times, the air took on an unsettled, nauseous feeling. I didn’t understand it. Wasn’t this a foolproof joke? Or were these people incredibly fond of frogs?

They weren’t, I don’t think. They just saw what I wasn’t self-attuned enough to understand.

The experiment shouldn’t have been about how many obstacles I’d surmounted: the frogs’ mating season, the underwater recordings, the creatures’ ill health. It shouldn’t have been about how many weekends I’d sacrificed, or how much sanity. It shouldn’t have been about the competitions, the awards, whatever skirt suits I may or may not have worn.

My ambition should have been directed toward discovery, not these shallow signs and accolades. And the frogs should have been compatriots I cared for and about—not expendable symbols of my own martyred self.

The last time I told the story was in a graduate school class a decade after the experiment. It was the first day of the course—a radio class—and my instructor had asked us to go around the table, introducing ourselves and telling a story. I meandered through the tale, the standard smirk appearing as I uttered the final line (“And then there was the frog who had a seizure, because I’d boiled him”).

Beside me, my friend laughed, a kind gesture. The rest of the class stared quizzically. “Well, that’s my story,” I said, by way of conclusion, and squirmed in my seat as a classmate started his own tale.

It was the last time I told it. After the class, I tried for the first time to figure out not why I hadn’t gotten laughs, but why I’d told the story at all.

The laughter would tune out the screech of recognizing how blinding was my need for approval.

There was a bit of bravado there, certainly. But I think there was also a subconscious awareness that my motives had been perverted, my ambition misplaced. If I succeeded in making the story into a joke, I could squash that awareness into oblivion. The laughter would tune out the screech of recognizing how blinding was my need for approval.

But in trying to banish the recognition, I’ve instead incited it to bloom. The screech, it turned out, was pretty loud. I’ve realized, after all these years, that blind ambition doesn’t mean much. You’re left with a story of an insane research project that you tell and tell, hoping to transform its meaning, and a heap of dead frogs.

Jessica Gross is a writer based in New York. She has contributed to The New York Times Magazine, The Paris Review Daily, and The Atlantic Cities, among other places.

Art by Lena H. Chandhok.