This week we present two stories from people who had hypotheses.

Part 1: Teaching sixth grade science becomes much more difficult when Xochitl Garcia's students start hypothesizing that fire is alive.

Xochitl Garcia is the K-12 education program manager at Science Friday, where she focuses on supporting the inspiring efforts of educators (of all types) to engage students in science, engineering, math, and the arts. She is a former NYC school teacher, who specializes in sifting through random piles of junk that she insists are "treasures," to figure out cool ways for learners to explore scientific phenomena. You can find her making a mess in the name of science education at the Science Friday office, her house, with other educators...you get the picture.

Update: Xochitl welcomed her baby (not fire) into the world on 1/1/2020.

Part 2: When journalist John Rennie is assigned to cover an entomological society event where insects are served as food, he sees an opportunity to face his fear of bugs.

John has worked as a science editor, writer and lecturer for more than 30 years. Currently, he is deputy editor at Quanta Magazine. During his time as editor in chief at Scientific American, between 1994 and 2009, the magazine received two National Magazine Awards. He co-created and hosted the 2013 series Hacking the Planet on The Weather Channel. Since 2009, he has been on the faculty of the Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program in New York University’s graduate journalism school. John is @tvjrennie and john@johnrennie.net.

Episode Transcript

Part 1: Xochitl Garcia

So, sixth grade, we’re in a six grade classroom, 603. We’re spending a week on the characteristics of life. Not a big deal. Living, non-living, no worries. And the basic premise is, to start this week out, we give them a bunch of examples of things that might be living, non-living, once-living, whatever. They're supposed to work together and it’s more about the discussion. It’s more about the discourse. It’s more about pushing each other and creating a schema.

And they're sitting at tables. They've already done these observations. They walked around the room. They messed with objects. They looked at videos. They collected. And they're sitting down and are starting to talk and we didn’t really have to do any prompting. I have a co-teacher, so we’re walking around the room.

They're asking each other questions, like, “Well, no. Like that thing got hot. Doesn’t that mean that it’s reacting to something? Doesn’t that mean it’s living? Doesn’t it violate one of your rules that you made? This rule is wrong.”

Xochitl Garcia shares her story with the Story Collider audience at University of Rhode Island as part of Inclusive SciComm in September 2019. Photo by Zak Kerrigan.

And they're having this really good debate and my co-teacher and I are like, “Oh, we killed this.” Like, “Kids are super into science.” Like, “Oh, my gosh!” And we’re like high-fiving each other.

I’m walking around the room and we’re observing conversations and I pass by a table and I hear, “Fire is definitely alive.”

Okay. Cool. This is why we do science in groups. This is why they're together at a table and we’re going to have a bigger discussion later. They'll push each other’s ideas. They'll challenge. It will be great. They're doing great science discourse. Their skills are amazing. I’m so excited.

So I leave that table and I just walk around and I forget about ‘fire is alive’. I think it’s going to go away.

And let’s just be clear. Fire, not alive. Right?

So sixth grade, we say life is GRIM. That’s what we... I think it’s funny. My co-teacher thinks it’s funny. Kids do not think this is a funny definition. So there are basic premises like they grow, they reproduce, they interact with their environment, they have a metabolism. Life is GRIM right? It’s great. But they're supposed to construct that knowledge. It’s not for me to give them. It’s the most effective way.

So we get to the whole class discussion and I have a little inkling. I have a thought. I was like, “’Fire is alive’ it’s going to be gone. It’s good.”

And we start categorizing and, sure enough, this table, we put fire up. Everybody is like, “Not alive, not alive.”

I’m like, “Great, great.” Like winning.

And then this table is like, “No, it’s alive.”

And like this one student took a table of four and convinced them that it’s alive. And I start to freak out a little in my mind. I’m like, “I’m that person people talk about. I’m that teacher that people talk about. Daily news: New York City Teacher Thinks Fire Is Alive. What an idiot.”

Like high school teacher is being like, “What did your teachers teach you?” Like, “Where did you come off with this idea?”

Xochitl Garcia shares her story with the Story Collider audience at University of Rhode Island as part of Inclusive SciComm in September 2019. Photo by Zak Kerrigan.

And I’m like, “Oh, my God. Oh, my God. What do I do?”

And they start questioning each other and I’m like, “Great, great. This is going well.”

And kids were like, “Well, they don’t reproduce.”

And this kid is like, “Bro, sparks. Sparks. Sparks are babies.”

I’m like, “Oh, my God.”

And they're like, “Sparks, they grow.” And they start to talk about all the things I just named. Growth. Right? They're like, “Fires grow. You see wildfires. They spread.”

They talk about nutrition. They're like, “They eat wood. They eat paper. They eat whatever.”

And my co-teacher and I are slowly freaking out, looking at each other across the room.

And so I’m like, “I can handle this. I've got this.”

I go to the front of the room and I’m like, “Do you see fire having babies?”

And the room gets silent. My co-teacher goes, “What the fuck,” from the back of the room. Just like mouths “What the fuck?”

And at that moment I had two realizations. One, we had an entire week on characteristics of life. We had planned inquiries. We had planned all these studies. They didn’t need the schema today. They were growing a body of knowledge. They needed it by Friday.

The second thing I realized is I just introduced a worse misconception to the students, which was that there's one paradigm of reproduction. I just told them birth was the thing. And now I’m going to have to spend a long time trying to take that visual of me birthing out of their minds.

I mean, this is all to say why did I freak out? Why was I freaking out? We were well planned. I was in my second year of teaching. I had gone to a series of PDs about how introducing misconceptions in science, like you don’t want to say the misconception to students because they will remember what you say. You want them to voice misconceptions.

I mean, it was all bad but I was trying to do the best I could. I was trying to really do it. It took a bit of... it was a moment of like being humiliated to learn something good, which was that I can’t control everything that goes on in the classroom and that’s not the point of teaching science. Right?

The point is to make space and opportunities for them to grow and grow their skills. Build their own schema for this amazing inquiry and maintaining wonder in the world. That was the thing I learned through this experience.

The other thing I took away was like that week kicked ass. At the end of it, they had an amazing discussion about artificial intelligence in robots where they applied these things that they had learned about characteristics of life but added these ideas of ethics and humanity, that we had not given them, to this analysis in order to bring some of their experience and some of what they value into the way we think about like what deserves our treatment of living.

And I’m seven months pregnant. I am not going to give birth to fire, hopefully. And not in front of students, although residents are students so learning is learning so maybe I'll be like, “Come on in. Great.”

And I’m thinking about this life I’m bringing into the world and one of the things that I really love is I love science and I like thinking about humanity and science and this idea that it’s not just a series of processes. It’s not these things on paper. It’s about the minds and the people and their thoughts and construction. That’s the kind of world that I want to bring a life into. It’s one where it’s about learning, it’s about being curious, but it’s about you in that experience building your knowledge.

Part 2: John Rennie

Listen. You seem like nice people so I want to be straight with you. I don't know what you've heard but I have never eaten a tarantula. Not even one. But if you're looking for a good recipe, there's one this spider researcher told me about that he swears by. You can write this down if you want.

So what you're going to do is you're going to start with a good average-sized tarantula and you're going to begin by soaking it in brandy for three hours. I told you this was a good recipe. So then you take out the tarantula and you're going to stick it under the broiler on each side for like five minutes.

Now, you're not trying to cook the tarantula at this point. You're just trying to singe off the urticating hairs on its legs which are highly irritating. And if you swallow them, you might go into anaphylactic shock.

So then you also, after you've done that then you carve out its two little venomous fangs and you put a stick, a skewer through the tarantula and you put it into like tempura batter. Then you just sort of lightly sauté it. Presto! There you have it. Fried tarantula. Serves one. I’m told it tastes like soft-shelled crab. Bon appétit.

As I say, I have never eaten one of these, but these kinds of recipes are the sorts of things you encounter when you wander into the world of entomophagy. That is to say the world of eating insects. That is something-- you're a little too nostalgic in the way you responded to that, sir. Yes.

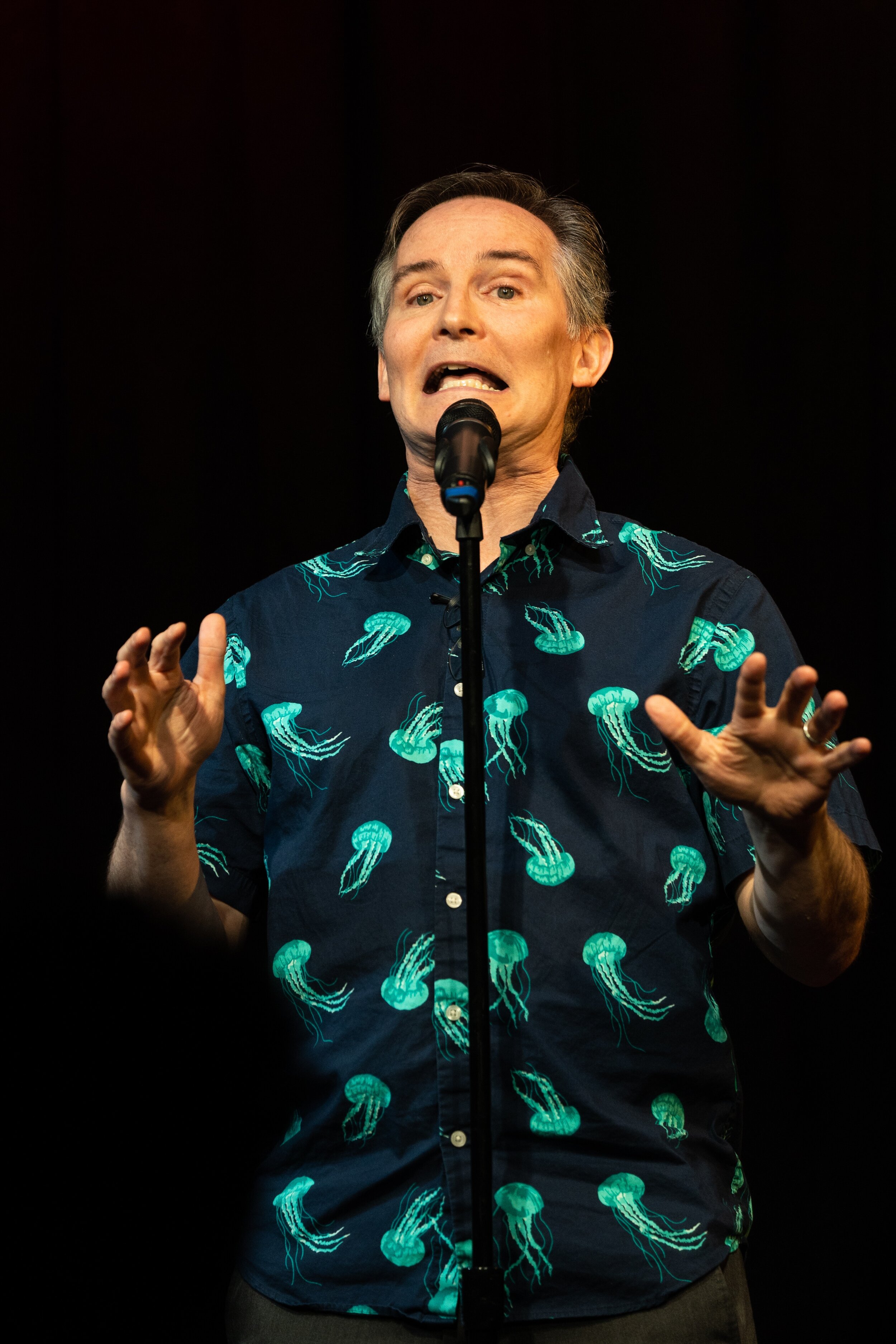

John Rennie shares his story with the Story Collider audience at Caveat in New York City in August 2019. Photo by Zhen Qin.

But I can get that because way, way back in May of 1992, I had my own encounter of this sort. I was, at the time, I was a staff editor and writer on the magazine Scientific American. Thank you. You can find subscription cards on the table, I’m sure. But also in that month, that was also the One Hundredth Anniversary of the New York Entomological Society, and they all decided they were going to throw themselves a big party.

And they decided to make this really interesting they would have it at the venerable Explorers Club on the swanky Upper East Side of Manhattan. And, to make it extra special, they would have a banquet where they would be serving insects as food.

Let me just make a note that on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, they are not commonly eating insects as food, even at the Explorers Club, at least that they know of. But let’s be honest. We are all eating insects. Yeah. No, we are. We have all eaten insects and not just because we have all been in convertibles or gone on picnics but because, remember, the Food and Drug Administration prescribes the maximum amount of insect parts that you can have in your breakfast cereal. So, trust me. We are all eating insects all the time.

And the reality is that outside of places like United States and Europe where this is kind of a fluke, really, most cultures around the world actually have real traditions of eating insects, because the fact is that there are millions and millions of people who depend on eating insects as a vital source of protein. And there are arguments that really all of us should be trying to subsist more on insect protein rather than-- you two need to get together after the show. More of us should be doing this sort of thing.

Now, these were the sorts of the tales that made this a great thing for me as a writer for Scientific American why it was that I proposed to my bosses that I go to the Entomological Society Banquet and participate in this and write about the experience and why I thought it was a great idea for me to do this.

What I did not tell my bosses at the time was that I also had a secret personal agenda. You see, I have always sincerely loved insects in the sense that I find them beautiful and I appreciate their importance to the ecosystem. I love insects - behind glass. I don’t like them flying around me. I don't like them crawling on me. I don't like squashing them because the buggy mess is disgusting. I don't care for this. It bothered me.

But somehow I got it into my head if I went to this Entomological Society, the banquet, and if I ate insects, it would give me a sort of mastery over this fear and I would triumph over it.

And so I set off that night. When I got there to the Explorers Club, the joint was jumping. Sorry. It was sincerely an unfortunate choice of words. No, really. Because, you see, they had 80 entomologists who were signed up to attend this. They would be eating the food at this banquet along with me, but there were three times that many reporters there. The place was, you should forgive the expression, swarming with reporters, all of them looking to find somebody who was actually doing this. Because there were so many reporters they could mostly just find other reporters, not people who were actually going to eat the insects. I however was.

Now, when I walked in, frankly, it really looked a lot like some of the high-society affairs. You had the string quartet playing chamber music in the corner and the open bar so the wine is flowing, which was good because the two things that I was sure of about this evening were I was going to be drinking heavily and, later, I was going to floss.

But, really, in most respects, it was just like any other big, elegant party. You had these formally dressed waiters walking around with silver platters. And they're walking up and, “Sir, may I offer you the Beetle Bread Bruschetta? Perhaps you would care for some of the Mealworm Baba Ghanoush? Waxworm Fritters with your choice of Plum Sauce or Mango Sauce? Perhaps you'd like the Chocolate Cricket Torte?” All real dishes.

But that’s not where I started. No. the first thing I decided to eat that night was I walked right up to this big wicker basket that was filled with roasted crickets and mealworms and waxworms, a huge basket of these things. Just sort of like a gigantic, oversized container of sort of bar snacks. I walked right over those and I grabbed a handful of them.

And the human mind is an amazing thing. When you look at any individual one of these roasted crickets, it really was not recognizable for what it was. But when you reach into a big basket of them and pull them out and all the other contents shift down to fill the space, the pattern recognition abilities of your brain are so great that you instantly see it as this huge skittering mass of insects.

So for me, the experience was just kind of like, “Oh. Da-ah!”

Now, I know. By now you are wondering, so, how did these taste? Honestly, they were quite good. These roasted cricket and the like, crickets are basically the six-legged tofu of the entomophagy world. Basically they have no real flavor of their own. They just take on the flavors of however they're being cooked which, in this case, would be oil and salt therefore delicious.

So if you ate these, really, you would not particularly know or object to it. In fact, in almost any of these cases where the insects were ingredients in the food, it was unnoticeable and completely benign and, honestly, you would think it was fine. And a lot of these things they tasted really quite good.

Not everything was great. There was this big witchetty grub. Any Australians in the room? No? That’s a sort of big larva. Picture something sort of like a big, pale, breakfast sausage with a chive for a head. That wasn’t great.

But I will tell you there was something that I thought was absolutely delicious, which were the honeypot ants. These have been flown in especially from Arizona. And these are like these little ants. Their abdomens are swelled up like little golden peas because they're filled with this honey-like nectar that they would hold for the other members of the colony. And they had these sitting in like a terrarium and you would go out and they would just take out one for you. It was like going to a restaurant and getting a lobster. That went in the corner.

That was nice. You pop it in your tongue and, really, it was delicious. It was like candy. It was wonderful. So I was really feeling great about the entire experience of how all this was going and I was on the road to mastery.

John Rennie shares his story with the Story Collider audience at Caveat in New York City in August 2019. Photo by Zhen Qin.

And then they brought out the final dish of the evening. And this, my friends, was sort of the pièce de résistance, because this was the giant sautéed Thai water bug. Essentially, a huge cockroach sitting on a plate looking like it was trying to run off of the plate, which I was hoping it might do. Because this was, sincerely, the quintessence of all of the fears I had about these insects. This was a giant, repulsive buggy bug.

And I saw it there on this plate and I picked it up and it had a heft to it, which was really disturbing, because it was about three inches long. Did I mention it was a giant Thai water bug? I picked it up and I looked at it. I actually felt this tremendous sense of inner calm. Because what I realized was I had been eating all of these other insects and I had been doing really well with that. And I could look at this giant Thai water bug and think I don't really want to eat this. I don't need to eat this. And I got ready to put it back on the plate.

In that very moment, I suddenly became aware of a gigantic halo of light surrounding me, the lights from all of the cameras, from all 250 of the reporters gathered there that night who had decided I was the one they had to capture on video eating the giant Thai water bug.

I felt trapped. Not unlike a bug in amber. That’s right. Keep your irony. There we go. So I really felt I had to.

But first I had to make the most gruesome choice of my life. Which end do I eat first? Because it’s too big to put in my mouth all at once. Do I eat the front end, with the antenna and all the legs and the little mouth parts? Or do I eat the back end, the big swollen abdomen full of some sort of buggy guts? Sort of ‘lady or the tiger’ moment, isn’t it?

My friends, I decided I would eat the front end first. Your approval means everything to me.

I closed my eyes. I opened my mouth and I bit down. And folks, this is how you discover that the universe is full of surprises, full of unexpected turns every day. Because, in fact, most sincerely, that bug was the most ghastly thing I had ever eaten in my life. It was a horror show. I mean the flavor is grotesque. It’s like cleaning fluid with a sort of acrid, burnt barbecue sauce thing going on.

But the flavor was nothing compared to the texture because, now, with each bite, the front end of this thing is turning into this giant swirling mass of disarticulating exoskeleton. Wings are poking me in the cheeks. I've got legs, actual legs stuck between my teeth now.

All I can do is just look out in all of these cameras and go, “Hah, good bug!”

I had not succeeded in managing to master my fear of these things. Quite the opposite. By trying to power through this, I had only succeeded in literally feeding the nightmares I feel to this day.

And in answer to the question that I know you have, no. The second bite was not any better. Thank you.