This week we present two stories from people who were confronted with what it means to lose family.

Part 1: After leaving class early, Sonia Zárate gets a startling phone call about her daughter.

Sonia Zárate is a proud Chicanx from SoCal. She is a mother and grandmother, Dodger-fan, trained plant molecular biologist and champion for diversity, equity and inclusion in STEM. As President for the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science (SACNAS) and a Program Officer for the Howard Hughes Medical Institute she is living the dream at the intersection of STEM and Culture. When she is not working to make the scientific enterprise excellent by making it more inclusive, she enjoys traveling, running, facetime calls with her family and playing crazy 8’s. You can reach her on Twitter @sonia__zarate.

Part 2: An indoor kid at heart, Sam Dingman goes on a hike anyways and ends up making a shocking discovery.

Sam Dingman is the creator and host of Family Ghosts, a storytelling podcast about familial myths and legends which has been hailed as a critic's choice by The New York Times, The LA Times, and NPR. Sam is a winner of the Moth Grand Slam, and his stories have been featured on The Moth Radio Hour, Benjamen Walker's Theory of Everything, and Risk!.

Episode Transcript

Part 1: Sonia Zárate

It's the first year of my graduate program and I am, in addition to doing research, taking an advanced cell biology course and a couple of different research seminars. I am going to leave the lab early that day because I'm headed to a Rage Against the Machine concert with my husband in LA.

So, growing up there were two different things that kids could do in my sleepy little town. They could either go to these backyard keggers or they could go to concerts. And I belong to the group that went to those rock concerts.

So it was such a relief for me then and it was supposed to be a release for me now, but I questioned whether it would be. You see, as a parent of a 7-year-old daughter, I always had to manage my research and everything else that I had to do between those daycare hours. So this outing was going to cut into those hours and I wasn't sure how I felt about that.

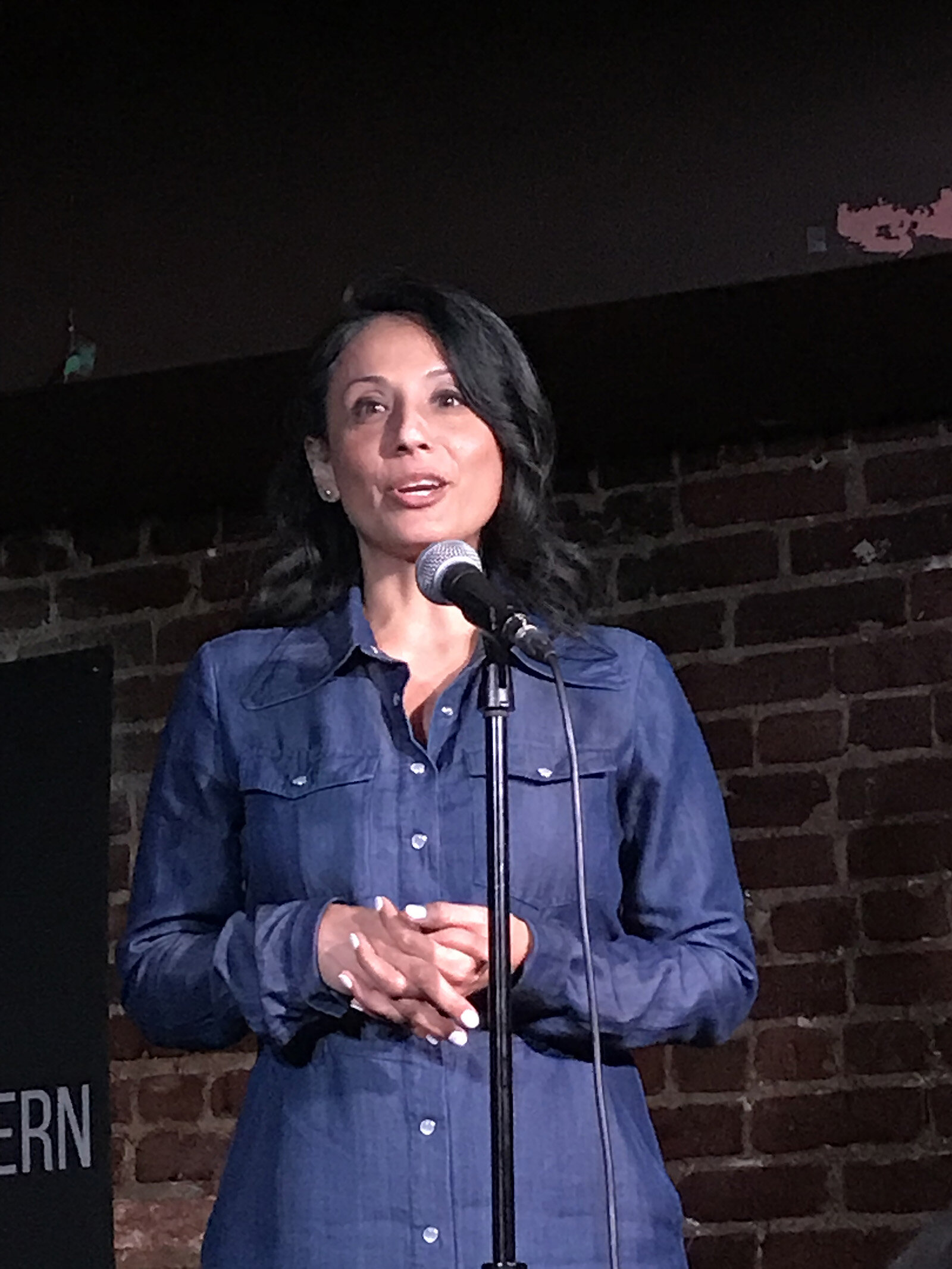

Sonia Zárate shares her story with the Story Collider audience at Bier Baron Tavern in Washington DC in August 2019. Photo by Mary Garcia Cazarin.

I had talked to my father and he had agreed to watch her. And when I called him the previous night, he let me know that his wife would be picking up my daughter from school as opposed to the after-school care. I knew my daughter was going to be super excited because even though she liked her after-school care, she liked her grandparents so much better.

So I reminded him and, yeah, he was going to pick her up.

The plan was that my husband was going to pick me up at the lab and that I was supposed to leave my rock concert outfit in his car. Truth be told, if he was not out in that parking lot waiting for me, I would have set up another PCR reaction. He would have been waiting for me.

We take off and I wait until it gets a little bit dark to change out of my frumpy lab outfit and into my cool rock concert outfit for this Rage show. At that time, my cell phone rings. I look over and I recognize the number.

I casually mentioned to my husband, “Leave it to my dad to always know when I'm up to no good,” like changing outfits in cars.

So I answer the phone, I say, “Hey, Dad,” and his response to me was, “Sonia, stay calm.”

My heart stopped and raced all at once. As it turns out, there had been a car accident and my daughter and his wife had been taken to the hospital. I fought off this feeling of just absolute dread as my husband and I weaved in and out of traffic. It was total rush hour traffic. We were weaving in and out of it. And even though we knew it wasn't going to get us there any sooner, I think it actually made us feel a little bit better to feel like we were doing something.

So getting to the hospital, these memories are kind of vague for me but I do recall that my husband dropped me off at the front door. Somehow or another, my dad was there to greet me. I must have called him.

As we walked over to where my daughter was, I searched his face. I'm not sure for what. But I braced myself as we walk through the curtain that separated her from the other patients in the emergency room. She had a gash on her forehead and there was blood all over her face and on her hands, but otherwise she looked fine. And so I started breathing again.

The scan, it told a different story. On one side of her face you could see her cheekbone. You could see that it framed her eye orbital. But on the other side of her face, it was completely dark. Her facial bones had completely shattered.

So this evolutionary adaptation to prevent the brain from damage from blunt force trauma was just supposed to be a good thing, but as a parent of this beautiful little girl, I had a hard time embracing that idea.

The next thing I remember, there was a team of surgeons telling me what the plan was, what we needed to do next and some nurse just seemingly came out of nowhere with forms for me to sign. You know, the consent forms. It was at that moment that I understood the severity of this situation. It was at that moment that I realized that in order to get through this nightmare that I was going to have to put my heart into an imaginary jar and handle this situation with my science identity, with my faith in science.

The surgery was supposed to last three hours. Nine hours later, the surgeons came out and they told me that there was many more fragments than they had anticipated but that they had retrieved them all.

Sonia Zárate shares her story with the Story Collider audience at Bier Baron Tavern in Washington DC in August 2019. Photo by Mary Garcia Cazarin.

I remember I had talked to my advisor. She had told me to drop all my courses, and I did drop all those research seminars, but I didn't drop that cell biology course. It was my refuge. Reading about cellular mechanisms and the experiments that led to the elucidation of these mechanisms was comforting to me. It made sense. They made sense, whereas this accident didn't make any sense at all.

During that surgery, the surgeons had made an incision across my daughter's head from ear to ear and they had peeled back her face in order to retrieve those fragments. And thinking about that, it was, wow. I didn't know that you could do that. But as her parent, that knowledge was absolute agony for me.

And so days went by, people came and went. There was a sound of that heart rate monitor and all the while I sat next to her holding her little hand saying to her, “I'm still here.” She was in an induced coma and that was the only thing that I could do was just hold her hand and let her know that I was still there.

My husband finally went home after three days and he came back with clothes for me. And when I opened the backpack to get my clothes, I noticed that he had brought toys for her for when she woke up. It's just incredible what shock can do. For him I guess he was in denial, and for me, I clung to science like there was no tomorrow. I just needed to do that.

So my daughter had a series of reconstructive surgeries. And in that process, she ended up contracting meningitis. At this point, she was combative to doctors and nurses. She was refusing to eat. She just stopped engaging. I had this sinking feeling, and the doctor confirmed it, at this point my daughter had lost the will to live. He had seen this before and he felt that what usually helps patients is the return of some normalcy in their lives.

And I got that, because that cell biology class, that's what that did for me. It gave me some sense of normalcy in this chaos.

He told me to take her home. So she went home with the PICC line to administer the cocktail of antibiotics that she needed to treat the meningitis. Four hours later, that PICC line failed. As I was carrying her back into the emergency room, I realized how fragile she was. She was seven years old. She weighed nothing. It wasn't even an effort for me to carry her back in.

And at this point, I was absolutely losing my faith in science. I was so banking on science to save her. As I walked through those emergency room doors, I was just pushing down these feelings that this could be the last time that she walked in or out of these doors.

Thankfully, those four hours made a huge difference. She became motivated. She started eating. And two weeks later, we went home for good.

I got a B-plus in that cell biology course. That was the lowest grade I got in my graduate career, but it was worth it. That class saved my life. That class and science really helped me be able to navigate this parental nightmare that I had found myself in.

It's been 20 years since that accident and, believe it or not, I just recently realized that I forgot my heart in that jar. I've been navigating life always waiting for some shoe to drop somewhere, or maybe I just felt that I wasn't going to be strong enough in order to put that thing back in and process this event.

I feel strong enough now so I'm taking my heart back. Thank you.

Part 2: Sam Dingman

It's a couple years ago and my girlfriend invites me to her family reunion. I'm very excited about this because my girlfriend does not yet know this but I am planning to propose to her, so I want to make a really good impression on the family. But there's a little bit of an issue with this, which is that her family is comprised primarily of what I like to call ‘outside people’ by which I mean people who like to spend time outside.

I am an inside person. I work in radio and podcasting, which means that I spend almost all my time in rooms that are scientifically engineered to deny the existence of an outside world. That's how much I like being inside.

But it's really important to me to make a good impression on this family reunion, so I say to her, “Well, I would love to go. What are some of the activities going to be?”

She says, “Well, we're probably going to do a lot of hiking.”

And I say, “Godammit.”

Sam Dingman shares his story with the Story Collider virtual audience on Crowdcast from his living room in upstate New York in July 2020.

But I agree to go and actually when I get there, it starts off really well because it turns out that in addition to a large contingent of outdoorsy types, there's also a significant number of old wasps in a basement drinking martinis. That is something I'm very good at. So I kick off the family reunion by hanging out with the wasps, sipping on the martinis which they're very good at making.

We're having a spectacular time until my girlfriend comes down and finds me in the basement two to four martinis in and says, “Hey, we're going to head out for that H-I-K-E. Do you want to get in on that?”

And I think to myself, “Sam, you have an option in this moment. You can stay here and do the thing you're good at and make a good impression or you can go on the hike at which you will almost certainly fail.”

I think, “Nope. You know what? It's important. I need to step up here.”

So I say, “Let's hike it up,” which I assume is the thing that hikers say.

So we set out on the hike. It starts off actually pretty well, kind of like the family reunion had. We get up to the top of this mountain. I'm pretty excited because I don't know anything about hiking but I assume getting to the top of a mountain is a goal.

So we're up there at the top of the mountain and I'm feeling pretty good about myself but all of a sudden things change for the worse and very abruptly. This giant bank of clouds rolls in. The sun disappears. It gets incredibly dark and it starts to pour down rain. Thus is the hardest, most torrential rain I have ever been in.

Now, for my girlfriend's family, no problem. These are outside people. They are wearing hiking sandals. They are wearing waterproof pants. This is not an issue.

I am wearing a blue button-down shirt just like this, a pair of khaki pants, dress shoes and a powder blue sport coat, because I was trying to make a good impression.

Thankfully, one of my girlfriend's cousins has an umbrella. He opens his backpack and he pulls out an umbrella and he says, “Would you like this?”

And I say, “Yes, there's only one way for me to look more ridiculous. Thank you so much.”

So I put up this umbrella and I look like the little girl on the front of like those salt containers, and we begin making our way down the mountain.

Sam Dingman shares his story with the Story Collider virtual audience on Crowdcast from his living room in upstate New York in July 2020.

And as we do, all of a sudden I feel this thing. I've never felt anything like this before, and this is the feeling. It's like the hand of God has reached out of the sky, grabbed the top of the umbrella, hoisted me into the air and then thrown me to the ground. And this feeling is accompanied by a sound like this, “Pfff.”

As I hear this sound, I look up and I see white light flashing by my periphery. Then I hear one of my girlfriend's other cousins say this phrase, and I will never forget this phrase. It really is locked in my memory. The phrase was, “Drop the fucking umbrella!”

I throw the umbrella to the ground. There is smoke coming off the top of it and I realize that I have just been struck by lightning.

Now, when you are an inside person, something people say to you sometimes is, “What are you afraid of going outside? You think you're going to get struck by lightning?”

But I don't really have time to think about that in this moment because, in this moment, right after I realize that I've been struck by lightning, I'm overcome with this other thought that I wasn't expecting which is I think I have to take care of my family. And I was completely surprised to have that feeling because, until this moment, I had felt no connection with them and had been scared that that was never going to be something that could happen.

But as soon as this has happened, I jump back up to my feet and I said, “Everybody, come here. Everybody, come here.” We run over into this little grove of trees where I imagine we'll be safe and we all look at each other. We're like, “What are we going to do?” And none of us has an answer because what do you do in that moment except hope you don't die.

Thankfully, none of us did. But for just that split second, we really were together. So thankfully, we get down to the bottom of the mountain without further incident.

Afterwards, my girlfriend and I are sorting through this experience. She was a PhD student so the first thing she did is look up the odds of how likely it is to get struck by lightning. And when we looked it up, the number we found was 1 in 15,300. So while it is more common than winning Powerball or getting attacked by a shark, statistically it's almost meaningless. It's just random.

But much like I do not understand how to dress for a hike, I also don't understand numbers. I am a storyteller. I can only understand the world through stories. And when something like that happens, it rewrites your entire story. And you want that to mean something.

Shortly after this, my girlfriend and I split up. All of a sudden, it's not just the lightning strike that feels meaningless. Everything feels meaningless. I was preparing to make the entire remainder of my story intertwined with hers. Now, that feeling has been replaced with this numbness and I'm just walking around feeling nothing all the time.

It's a short while after that and I'm in a group of people and I tell the story of getting struck by lightning. At the end of it, this woman comes up to me. She's an older woman and she's kind of frail. She grabs my forearm and she says, “Are you a Buddhist?”

And I say, “No. What's about to happen?”

And she says, “Listen to me. What happened to you is a blessing. It's called a darshana. You are a holder of light.”

Then she disappears. I'm not 100% convinced she was ever there, but I remember her saying this.

I realize again, after another inexplicable incident, Sam, you have an option here and that is to decide that what she has just told you is the lesson that you are supposed to learn from this lightning strike, which is to say that day when I went up to the top of the mountain, I was metaphorically, and it turns out literally, grabbing on to a lightning rod. I cared about this person so much that even though I had almost nothing in common with them I wanted her family and all of their pockets and sandals to also be my family. It didn't work out that way but for a split second after the lightning strike, I got a little sense of how powerful that feeling might be. And I now know what I have to look forward to when that does happen with the right person.

So I have decided that from now on, whenever I have the option, no matter how much it hurts, I'm going to choose to hold on to the light. Thank you.