In this week’s episode, both of our storytellers share tales that illuminate the transformative power of returning to their roots.

Part 1: Gregor Posadas joins the army to pursue his dreams of becoming an engineer and fulfill his father’s wish of “fixing” their home country of the Philippines.

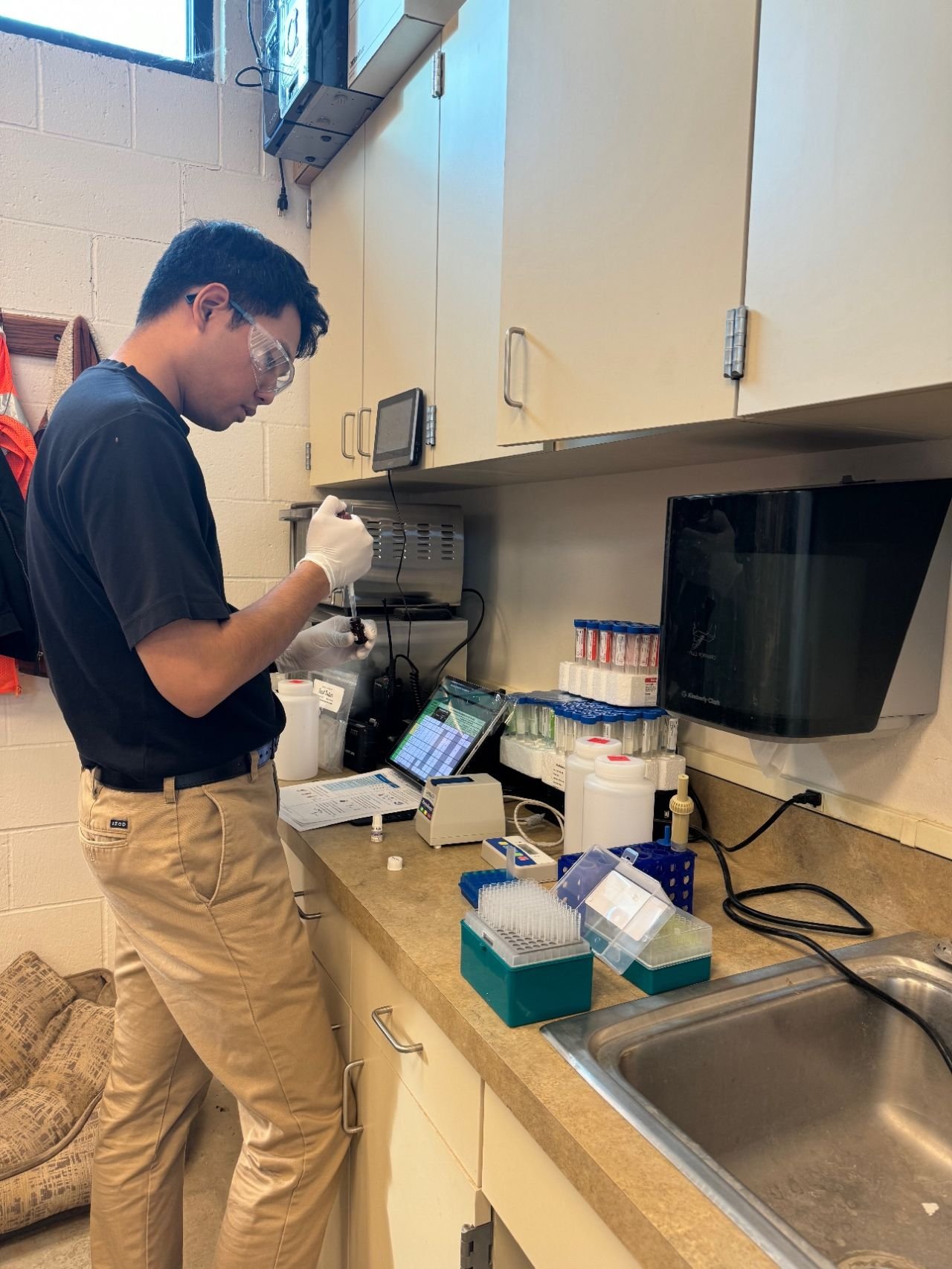

Gregor Posadas is a Civil Engineering student and Undergraduate Research Assistant at Boise State University. He is currently set to graduate from his undergraduate studies by December 2023. Born and raised in the Philippines, he grew up with a strong interest and deep appreciation for science and engineering, thanks largely in part to the influence of his late father Dr. Roger Posadas - a former relativity physicist, professor, and chancellor of the University of the Philippines. Gregor is committed to learning about new technologies in water/wastewater treatment, sustainable infrastructure, and water resource systems in developing countries. He specializes in data analysis and environmental engineering. He is set to begin his masters studies at Boise State University in the Spring semester of 2024, immediately following his undergraduate graduation.Outside of his studies, Gregor also currently serves as a Combat Engineer in the United States Army Reserves. He enlisted in 2019, just eight months after moving from the Philippines to Idaho. Gregor also serves as a Graphic Designer and Marketing Delegate for the Boise State Martin Luther King Living Legacy Committee - Boise State's student agency in charge of organizing the annual MLK Day March in Boise, Idaho.With a unique upbringing and an diverse set of experiences, Gregor is an engineering student with many interesting stories to tell.

Part 2: After losing his father as a young child, Nandhu Balakrishnan feels compelled to use his school savings to buy a life saving drug for a patient at the hospital he’s working at.

Nandhu Balakrishnan works for Georgia Public Health Laboratory as Director of Microbiology. His job involves public health and community service. He was born and raised from Southern India. He completed my Master’s and PhD in Medical Microbiology from India. In 2008, he migrated to United States and worked as post-doctoral fellow before he landed into a real stable job. His passion towards laboratory science has stemmed from his childhood and it has been a roller coaster throughout the years to climb to the pinnacle of success. He loves cooking with authentic spices and enjoys feeding people.

Episode Transcript

Part 1

In 2019, I had to put a pause on my high school studies in the Philippines to move 7,000‑and‑something miles to the amazing city of Boise, and the future seemed very uncertain. The only thing I was sure of was that I wanted to be a civil engineer.

See, when I grew up, my father, who was a physicist and a professor, had urged me very early on to pursue a degree in engineering. I think I told him once that I wanted to be a painter, and, oh, my God, the look of disgust and disdain and disappointment on his face. He was effectively telling me that, “Oh, my gosh, you wanna be a painter? You're gonna retire homeless.” Fair enough. So, from that little anecdote, from that point onwards, I was very blatantly urged by my parents to pursue a career in civil engineering.

Now, that may seem very appalling. I mean, forcing your kid to pursue a future that he didn't choose. But, to their credit, I did like playing with Legos and Minecraft and, yes, I am from that generation.

On the other hand, my dad had told me that engineering could help fix our country, the Philippines. Whenever there was a bump on the road that our car would hit or we would get a notification in the mail saying that there's going to be a water shut off, or if there was news of failing infrastructure in the country, my parents would give me this look, effectively saying, “Please, oh God, study hard so you can fix the country.” So, that was the type of family that I grew up in.

But the other thing that you should know about my family is that my family was poor. Even though my dad was a professor, he wasn't making much. And so when he passed away in 2017, the only inheritance he had left us was my inspiration to become an engineer.

My mother, a widowed housewife with no job and two young kids to raise, had decided that it would be in our best interest to move to America. I was very much against it. I mean, I had grown up with the notion that my future would lie in helping our country, but how on earth could I help our country if I wasn't in it in the first place?

And so, very heated arguments were exchanged between my 16‑year‑old self and my mother. The very fact that I'm talking to you right now here at Boise State University should very clearly tell you who won those arguments.

So, we moved. In 2019, I transferred to some random high school here in Boise. And I'm not going to lie, I was very much a loner. In between the cultural differences between high school in the Philippines and here in America and the fact that I was an introvert, it was very hard for me to find friends.

So, I had decided that up until I graduated high school, all I would do was study, and that's what I did. I studied and studied and studied all the way up to graduation.

Gregor Posadas shares his story at Boise State University in November 2023 at a show sponsored by Boise State. Photo by Joseph Rodman.

Graduation came. Next stop, university.

At the time, my mother was working as a grocer at the local WinCo downtown and her job was to stock up cereal boxes up on the store shelves. That was the only source of income our family had.

So, when I told her that I wanted to go to university, she very gently told me that we just couldn't afford it. I was very upset.

Now, granted, I could have looked for a job, but, remember, I had only been five months into this country. I had no car, no direct deposit. I didn't even know what direct deposit was. I didn't have my citizenship and I didn't have my social security, so the cards were pretty much stacked up against me.

My mother one day, she sits me down. She had just gotten home from her groceries and she hands me this brochure. In bold letters it said, "Go Army."

She told me with a smile, she was like, "They'll help pay for your college."

And I was like, "Woman, whoa, whoa, whoa. I have only been in this country for five months and you now want me to serve in the army of a country that I barely know."

And she was like, "Yeah.”

Of course, I was against it but, like most arguments with my mother, this one saw me sitting down at the West Franklin Road Army Recruiting Station.

I told the recruiter, "Yeah, I want to enlist so that I can go to college and get my civil engineering degree."

And my recruiter, who funally enough was also Filipino, they told me, "Oh. Oh, civil engineer. Do you see this? Combat engineer. That means it's practically the same thing.”

And I was 17 at the time. I didn't know any better. So I was like, “You know what? That sounds like a good idea. I'll sign up to be a combat engineer in the United States Army.”

To the veterans and service members out here, you'll know very well that I had just made a crucial mistake. Little did I know that combat engineers were supposed to be in the front lines of whatever, but there I was. By the time I realized the mistake that I had made, it was too late.

Come January of 2020, a year after I had moved here to America, my shaved head and I were undergoing basic combat training in Fort Leonard, or Fort Lost in the Woods for the more familiar of you, in Missouri. In between the countless miles that we rucked and the yelling from the drill sergeants to do push‑ups, I had to constantly remind myself that this was all so that I could be a civil engineer. Effectively, at some point, I realized that I had to learn how to serve this country so that I could effectively help my country in the future.

Come April of 2020, I was done with training, I got back to Idaho, and I was pretty much set to go to college, thanks to the tuition assistance and the GI Bill. But it didn't pay for everything, so I had to do a bunch of random odd jobs on campus. At some point, I was a barista, a graphic designer, a dispatcher, I don't know what the heck I was doing as a video game tester, but there I was. I was also an IT specialist, telling people to turn on and off their computers, and there I was, doing all these random jobs and have to constantly remind myself that this was all so that I could be a civil engineer.

But just as the Army had put me into school, it was also the very reason why I had to take a break from it. In 2022, I had to go to the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, California to undergo a month‑long training event, which would effectively pull me out of school for a little bit.

During that time, in between the random sandstorms and the flash floods that would occur in the middle of a desert and the countless miles of concertina wire that I had to help picket pound into the ground, I had an epiphany. I do not want to be doing this for the rest of my life.

I sort of started thinking, “Okay, what's the next rational step? I'm a civil engineer student. How do I get to becoming a civil engineer?”

So, I realized that I needed to get an internship. That was my biggest goal for 2022, get an internship, get a civil engineer internship. That was the only thing I had set my mind to. As soon as I got back to Idaho from that training, I wasn't in school, so I couldn't do any of those random ass student jobs that I had mentioned earlier, so I had to get a dead‑end night shift office job, which was a 4:30 PM to a 1:30 AM‑type of deal.

I hated that job. I dreaded going to that job every evening. And so every time I would get home from that job, I would spend the next two months just applying to at least five internships a day. It didn't matter if it was in‑state, out‑of‑state, Nampa, Meridian, wherever the heck it was, I would apply for it.

I remember out of all the internships that I had applied for, none of them would hire me. Only three of them, three of them in town had responded to my application saying, "Hey, we want to do an interview with you."

So, I went to those interviews in random cities here in Idaho and all of them would come back with a response saying that we had found a more qualified candidate. And so in between the rejection and my homesickness, I was pretty much out of it.

So I had decided with what little money I had left, you know what? I am going to go fly back to the Philippines. I cannot be dealing with this right now. I'm on the verge of giving up on my future in engineering and I just can't, so I flew back home.

During my self‑imposed Thanksgiving break in the Philippines, I had gotten an email from this company named Stantec, which I would later on find out was one of the world's biggest water infrastructure design firms. I was surprised because I was thinking, “Okay, look, none of these local companies would hire me, but this huge international firm wants to take me under their wing? That sounds insane.” But I bit the bullet.

They had scheduled an interview with me at 1:30 PM Mountain Standard Time. Now, I say that very specifically because, mind you, I was still in the Philippines. So, come the day of the interview, these random engineers who I'd never met started pouring into the Zoom call.

One of them asked, "Gregor, why is your window so dark?"

I told them, “To be frank, it's 4:30 in the morning here in the Philippines.”

Gregor Posadas shares his story at Boise State University in November 2023 at a show sponsored by Boise State. Photo by Joseph Rodman.

They were all pretty shocked, but at the same time they commended me for still being able to make it to the interview. We went on with the usual interview procedure. I had told them that the closest thing I had to engineering experience was my experience as a combat engineer. And I will tell you right now that it is very difficult to justify how blasting doors open and shooting guns is related to designing a wastewater plant.

The interview stopped. We all went our separate ways and I flew back home to Boise feeling very anxious, because I wasn't sure if I had a job waiting for me.

So, three weeks after I had gotten back to Boise, I get another email. Again, it was Stantec, telling me that they wanted to do a breakfast interview with me.

I was like, the first thought in my head was like, “Okay, geez, how many interviews do these guys want?” But the next thing was that, “Okay, okay, this is my in.”

So, come the day of the interview, it was at this local diner. I remember the engineers who did the breakfast interview with me had treated me to a quesadilla, and that was the first time in my life that I ever had a quesadilla, so there were a lot of monumental things going on on that day.

But we went on with the normal interview procedure. They asked me how my trip was, what my plans for the future were, and that was that. We had all left the diner doors, ready to go to our cars and go our separate ways.

But then the senior principal engineer who was part of the interview stopped me and he asked me, "Uh, Gregor, who are we in competition with?" Effectively asking me who else I had applied for.

I stopped for a moment and I said, “Uh, no one. I mean, the only company I'm talking to right now is yours.”

And he gave me this very confused look and he was like, “Oh, okay. Well, good luck to you then.”

So we all went our separate ways. I went back to my car. But as soon as I sat down on the driver's seat, I had just realized how stupid my response was. The only thing I was thinking at that time was that, “Jesus Christ, now they're gonna think I'm desperate, that no one else is willing to hire me.” I was so disappointed in myself. On the drive home, I was disappointed. That night, I was disappointed. I woke up, I was disappointed. I think for breakfast, I had applied for five internships because I was ready to get that rejection notice from them.

But then come the afternoon of that day, my phone buzzes. I look at it. It's a Gmail preview. It says, "Stantec, Offer of Position."

And before I could open that email, I get this phone call. It was one of the engineers who had interviewed me.

I answer it and he's like, "Hey, Gregor, I just wanted to say congratulations. I'm sure you've read the email."

I'm like, "Okay, no. It's only been two seconds since I've seen it," but he just wanted to say congratulations because they wanted to move forward with my application.

At that point, I was hired. That was the first ever civil engineering job I had ever gotten and I was so proud. The effort that it took to get to that very point, and an internship doesn't seem like such a significant thing, but to me it was huge. The effort that it took to get to that very point didn't start with me handing them my resume over LinkedIn. It started with me reluctantly moving to the United States, transferring into some random high school that I wasn't familiar with, joining the military, taking on these odd jobs and going through random sandstorms and picket pounding in the desert, it took all that effort for me to get to that very point where I was hired.

After that phone call with one of the engineers who would later on be my supervisor for my internship, I immediately called my mom. In Tagalog, I told her, "Ma, natanggap ako," which means an English, “Mom, I got hired.”

She was so happy. She said, "Oh, salamat sa Diyos," which means, “Thank God,” and I'm like, “Okay, God didn't do any of the effort. I did," but she was so happy.

Because this was the plan. This was the whole reason why she had brought her two young kids to America, this very moment where I got hired. My future seemed a little brighter.

And here I am, talking to you guys about how I got my first internship. On top of my internship experience, I'm also now, as you guys heard earlier, a research assistant under the civil engineering department, where I get to learn a lot about wastewater. Just last week, I was at a wastewater plant, so I'd like to thank everyone in this audience for helping contribute to my research. If you understood that joke, that's disgusting.

But, here I am, one month away from graduation for my civil engineering degree. The only thing I had brought with me throughout this entire journey, even when the path didn't seem so straightforward, was a dream of helping my people through engineering. Those bumps in the road, those water shortage notifications, those failing infrastructures that would show up on the news that my father would complain about when he was still alive, my hope for the future is that I may one day go back home to my country and pretty much put my money where my mouth is and help fix those problems. See, at many points throughout this journey, I could have given up, but, as the saying goes, you can kill the dreamer, but you can't kill the dream.

Thank you all for your time.

Part 2

I was born and raised in a small, beautiful village in southern India. I lost my father when I was six years old. I still am not able to remember how my father looks like.

I still have this pain inside me and, during those childhood days when I go to school and see other kids in my age, my heart was broken. So, I always asked this question inside me. “How a true father really is.”

It has never been fulfilled. One day, definitely, I'll meet my dad.

On the other hand, my mother was a source of my inspiration. She instilled the motivation in me and she showed me the willpower that even I can be successful in this world.

My mother worked in my village and she worked for daily wages. She makes sure that we have food on the table. Most importantly, we struggle a lot financially. For example, my first pair of shoes my mother bought was after graduating my 12th standard back in India.

So, literally, for my education and my sister's education, my mother decided, “Okay, let's move out of this village and go to a bigger city.” So, we moved out of her village.

Nanduh Balakrishnan shares his story at The National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, GA in March 2023. Photo by Jason Abreu.

Then my passion was always to go to med school. I want to be a doctor. I want to be a surgeon. Unfortunately, because of my financial commitments that I can’t go to med school. However, by God's grace, I got a full scholarship in one of the premier institutions in India where I could pursue my Master’s in medical microbiology.

After my graduation, I started working as a microbiologist and, also, I just wanted to do a PhD. Because of my family situation and financial expenses, I couldn't continue my PhD immediately. So, I was working at the hospital as a microbiologist so I could save some money for my family expenses and for my PhD education as well.

Luckily, I got a full scholarship again to pursue my PhD in medical microbiology in one of the premier institutions, so I started my PhD.

I was at the hospital. I was at the blood culture bench. I received a call one day morning from the cardiothoracic emergency department.

“So, we have a patient. Chief asked me to call you because this could be one of the potential cases for your PhD.”

I said, “Okay, that's great.”

So, I just went up there. The patient was gravely ill. He underwent a valve replacement surgery in the same hospital and he was very toxic. His blood counts were all over. His kidneys were shutting down.

They asked me, they said, "Do you want to do a blood culture?"

“Absolutely.”

So, I sat with the patient. I drew the blood culture and I went back to the laboratory.

Next day, all three sets came out positive. We did the Gram stain. It was a Gram‑negative pleomorphic coccobacilli.

Subsequently, the culture grew multi‑drug resistant as Acinetobacter baumannii complex, which was susceptible only to one drug, imipenem.

I took the report to the hospital and they were doing rounds, so I gave it to the attending.

He looked at the report. All he said, “Unfortunately, I do not have this drug in the pharmacy.”

All I know at the time is that this patient is going to die if we don't treat this patient.

Nanduh Balakrishnan shares his story at The National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, GA in March 2023. Photo by Jason Abreu.

Immediately, the attending physician told directly to the patient, “If you don't get this drug from the outside pharmacy, you're going to die.” This guy was a 26‑year‑old farmer in a village.

Then he was crying and sobbing. He had his wife and she was holding a six‑month‑old baby in her hands. He didn’t know what to do.

The cost of the drug imipenem back on those days was $25, which was equivalent to close to 2,000 Indian rupees. That was just one quarter of his monthly wages.

He was crying and sobbing and I do not know what to do.

After that, he asked me, "Do you have a minute? I just want to talk to you."

I said, "Sure, why not?" I just pulled a chair and I sat next to him.

He was holding my hands. All he said was, "I already have so much debt in my life. I don't have this money to purchase the drug. I don't want to take additional debts on my shoulders. I would rather die." He started sobbing and, again, the wife started crying.

At that moment, I do not know what to do. I just went home.

On the same night, it's me, my mother, my sister and my grandmother. We all are having dinner. My mother was my father, mother, mentor, coach, and she's everything to me. I started sharing about this farmer, and then she started talking about my father.

She said, "I did not really tell both of you,” to me and my sister, “what happened to your father. He was gravely ill.”

Nobody came forward to financially support my mother, including my own family.

“If I had the money with me, I could have taken your father to a good hospital where I could have saved my husband and given you father's love, what it is.”

It was so painful for me. And all she said was, "I will let you decide what you want to do."

My grandmother was also there. My father was the only son to my grandmother. I know how painful it was to losing her only son, seeing me and my sister and my mother going through all these pains in our childhood.

And all she said was, "Now at least you have some savings that you can do this to this family. You can save this person so he can be a husband and he can be a father. I don't want any child to go through the pain that you have gone through in your childhood."

It was just resonating in my ears. I couldn't go to sleep. I could see myself in the six‑month‑old baby and I could see my mother in his wife's eyes, that pain that she's going to go through that my mother has gone through during my childhood.

Next morning, I went to my bank. I pulled some of my savings that I saved for my education and for my family expenses.

All I did was I took that money. I gave it to his wife. “Just go purchase the drug.”

She purchased the imipenem drug and they started the IV infusion immediately. You can see his blood cell count was dropping off as blood urea nitrogen and creatinine was going down. And I also connected them with the non‑profit organization where they could get some additional monetary support for the rest of their expenses at the hospital.

The farmer was completely all right. He left for home with his wife and the six‑month‑old baby.

The six‑month‑old baby is now a 19‑year‑old son who is doing engineering. And even though his father was an uneducated person, he was able to give the best education for his son.

And every time when I visit India, I visit this family to make sure they are doing okay. This is my first patient during my PhD and this has turned my life of who I am right now.

Most importantly, I've lost a lot of patients during my PhD period. We had a lot of cases who died with poor surgical complications for the valve replacement, but this patient was such a moment in my life, resonating my life in the past, in the childhood that he has gone through with.

So, we, my family, my mother… actually, I am not even able to remember how my father looks like. All I remember is just seeing his picture. We buried our father in my hometown in his own farm and we planted a neem tree. It was a big tree now. It was almost 25 years since I lost my father.

Nanduh Balakrishnan shares his story at The National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, GA in March 2023. Photo by Jason Abreu.

Whenever I visit India, myself, my mother and my sister, we go to our hometown and we cherish our moments under the neem tree.

Myself and my sister still owe a lot to my mother for the sacrifices that she has made for me and my sister. That has meant a lot to me. Even though my passion is I just want to be a doctor, but the drive and the motivation and the positive spirit she gave on to me, I have chosen this trajectory as a microbiologist and a public health scientist. And I continue my passion in saving lives.

At the end of the day, behind the scenes, each and every one of the laboratory professionals bring so much to the table. It does mean a lot. Even though this pandemic has been challenging for a lot of people, so many of them have lost their loved ones, but still, you all bring the positive motivation and drive the ship. And each and every day, each and every one of you are saving lives behind the scenes.

Thank you.