There’s rarely an expected path in science. This week’s episode, produced in partnership with The Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology, features two stories from scientists of their cutting-edge research institute at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who took unexpected journeys to get where they are today.

Part 1: After a troubling personal experience with the health care system, Heng Ji decides to try to fix it.

Heng Ji is a professor at Computer Science Department, and an affiliated faculty member at Electrical and Computer Engineering Department of University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She is also an Amazon Scholar. She received her B.A. and M. A. in Computational Linguistics from Tsinghua University, and her M.S. and Ph.D. in Computer Science from New York University. Her research interests focus on Natural Language Processing, especially on Multimedia Multilingual Information Extraction, Knowledge Base Population and Knowledge-driven Generation. She was selected as "Young Scientist" and a member of the Global Future Council on the Future of Computing by the World Economic Forum in 2016 and 2017. She was named as part of Women Leaders of Conversational AI (Class of 2023) by Project Voice. The awards she received include "AI's 10 to Watch" Award by IEEE Intelligent Systems in 2013, NSF CAREER award in 2009, PACLIC2012 Best paper runner-up, "Best of ICDM2013" paper award, "Best of SDM2013" paper award, ACL2018 Best Demo paper nomination, ACL2020 Best Demo Paper Award, NAACL2021 Best Demo Paper Award, Google Research Award in 2009 and 2014, IBM Watson Faculty Award in 2012 and 2014 and Bosch Research Award in 2014-2018. She was invited by the Secretary of the U.S. Air Force and AFRL to join Air Force Data Analytics Expert Panel to inform the Air Force Strategy 2030. She is the lead of many multi-institution projects and tasks, including the U.S. ARL projects on information fusion and knowledge networks construction, DARPA DEFT Tinker Bell team and DARPA KAIROS RESIN team. She has coordinated the NIST TAC Knowledge Base Population task since 2010. She was the associate editor for IEEE/ACM Transaction on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, and served as the Program Committee Co-Chair of many conferences including NAACL-HLT2018 and AACL-IJCNLP2022. She is elected as the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL) secretary 2020-2023. Her research has been widely supported by the U.S. government agencies (DARPA, ARL, IARPA, NSF, AFRL, DHS) and industry (Amazon, Google, Facebook, Bosch, IBM, Disney).

Heng Ji is supported by NSF AI Institute on Molecule Synthesis, and collaborating with Prof. Marty Burke at Chemistry Department at UIUC and Prof. Kyunghyun Cho at New York University and Genetech on using AI for drug discovery.

Part 2: When Brendan Harley is diagnosed with leukaemia in high school, it changes everything.

Dr. Brendan Harley is a Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His research group develops biomaterials that can be implanted in the body to regenerate musculoskeletal tissues or that can be used outside the body as tissue models to study biological events linked to endometrium, brain cancer, and stem cell behavior. He’s a distance runner who dreams of (eventually) running ultramarathons. Follow him @Prof_Harley and www.harleylab.org.

Episode Transcript

Part 1

One day in March 2020, we were already sent home for lockdown and I was struggling to build a normal work life routine at home. I was holding Zoom meetings with my students and collaborators, taking some online yoga classes, cooking for my son and organizing some online parties to connect with my friends.

Up until then, even with the pandemic I was a young, successful, even privileged artificial intelligence researcher with a very loving family and a highly supportive work environment. My life was nearly perfect.

In the middle of all of that, I got a phone call from my gynecologist. She said they found flat cells in my mammogram pictures which might be indicators for breast cancer and I should go to the hospital immediately to talk about whether I should do a surgery or not.

So the purpose of surgery is to do excision surgery and take out the flat cells. And I need to make my own decision whether I should do it or not.

I was of course in complete shock and I had a very hard time to process this message. I was wondering what if I die after a few years? What about my son? How would he live without me? What if I get an ugly scar from the surgery? Who should be in charge of my project meetings that I'm going to miss?

And because it was during pandemic, no other family members were allowed to enter the hospital with me. So I was in a very freezingly cold room in the hospital. I was pondering whether I should do a surgery or not.

The only other person in the same room was my surgeon, a tall and goodlooking man. He introduced himself to me. He said he has the same first name as one of my best friends at that time and he told me he's affiliated with the UIUC as a faculty member. He also published many papers on breast cancer.

So I was feeling very cold and I really hated the very bright lights in the room. So the surgeon asked the nurse to give me a very warm blanket to cover my upper body.

This is the university hospital. One really good thing is that they have some special techniques to warm up blankets. I asked for one more blanket to cover my leg and, half an hour later, I asked yet another one to cover my shoulder.

The surgeon noticed that I was very nervous so he asked three more blankets to wrap me up like a silk worm.

His professional background and that super kind attitude really gained my trust so I looked up at him and I asked him, “Do you think I should do the surgery?”

And he said, “If you were my sister, I would suggest you to do it.”

So I made my decision to do the surgery immediately and I was sent from this room to another surgery room right away.

What he said was of course a very reassuring remark on that particularly depressing day, but also I kept wondering why this kind of medical decisions, very important decisions should be made in such a subjective way. Would a decision be any different if I met a different doctor or surgeon?

Eight hours later after my surgery, I woke up in a very different room, although it was still very freezingly cold and scary. And I heard a more depressing news from my doctor. She said even though I did my surgery and my biopsy results were negative, I still need to take a medicine. That medicine is supposed to kill breast cancer.

I was shocked because I did not have cancer. Why should I take the medicine?

So she said my risk level is right above a threshold based on their machine learning model. The machine learning model is used to predict the risk level for breast cancer.

I'm a computer scientist. I have an instinct that I need to see the machine learning model and I want to know what kind of indicators they are using, so I insisted that I want to see the system. She agreed and she opened up the system on her computer. I looked at them and there are about seven or eight coarse grain indicators were used for this prediction model. And this model is supervised by very highly biased data, basically they collected mammogram data for older women from developed countries.

So because of my AI knowledge, I immediately found many problems on these indicators. They are ____ [00:05:04] screened. For example, some of them about the patient's profile, your age, race and gender and so on, and many of them are about unknown categories for many of us. For example, there's a question, “Are there any other women family members who also have abnormal mammogram results?”

So for a patient like myself, my grandma passed away about 10 years ago. She did not have access to mammogram. She did not probably ever do mammogram. So for this kind of category, I have to put a blank answer or just guess yes/no.

The other problem is a lot of the indicated results are not robust. Basically, if they change the number, for example, from a number of biopsies from one to two, in my case my risk level went up from 17% to 37%, even though all of my biopsy results were always negative.

Since then, I have decided to devote my research to help healthcare and medicine using my AI knowledge because I want to know what's wrong with my body, how to treat myself and everyone else who's in the same situation.

I am very nervous and scared to enter this new field that I know nothing about. I know nothing about chemistry, medicine or biomedical domain. Just like when I came to the country when I did not have any friends or family, but I'm so excited to have this great opportunity to learn new knowledge and also potentially change the world.

I have just started this new direction and I cannot wait to see what happens next.

Thank you.

Part 2

I grew up in a leafy suburb of Boston, Massachusetts, the oldest of three boys. My dad was a civil engineer who built water systems and my mom was an occupational therapist.

I built a lot of Legos and remember visiting my dad's office on school breaks. I was excited about the idea of doing something useful for society and, to me, that looked like engineering. There was no existential threat.

One of my first jobs was at a farming cooperative in my town, growing vegetables in the summer and tapping trees and making maple syrup in the winter. Worries were things like me not getting into my top choice college. It was all there, laid out in front of me.

But in life, sometimes there are crises. For me, that came in 11th grade. That spring was a whirlwind. Spring track season, college visits, junior prom, but I was just tired. I have been feeling increasingly tired for a couple of weeks. Spots appear to my vision. My times in track were getting slower and all I wanted to do after dinner each night was to fall asleep.

I put it off this junior year and didn't tell anyone. Then I woke up the morning of May 5th 1995, a Friday. Petechiae had to appeared on my hands. I scrubbed them off before coming down to have breakfast.

But my mom could tell something was off. She took me out of school and dragged me to a doctor's appointment that morning. She was convinced I was just not me. But I was too busy to admit to anyone just how tired I felt. I had a multiyear run of not missing any days of school, so after a quick test for mono, I went back to class.

I had college entrance exam Saturday morning so after track practice I went home, wanting nothing more than to go to sleep and feel better in the morning.

I had the flu a few months before. I slipped that off, ran the hurdles in the state national meet the next morning and got a Big Mac with my dad.

I was lying down in my dad's office crunched into a tooshort, blue leather sofa with my legs hanging over the end

I was uncomfortable in trying to get away from the noise of dinner.

The phone rang. I could hear the stress in my mom's voice then the house exploded with energy. Leukemia.

This was pre-Google. No information, just a voice telling my mom to get me to the hospital, any hospital. I was 17 and ignored just how sick I'd become.

My blood counts were bad, like historically bad. If I had gone to sleep that night, I probably wouldn't have woken up in the morning. So my mom scrambled to find a family friend who could watch my younger brothers who were just 10 and 14 and figure out a way into the hospital.

My dad was still at his office in Boston, so enter Larry, our neighbor. I'm still not sure why my mom didn't just drive us the 30 minutes to Brigham and Women's Hospital.

But my mom had told the voice on the phone we were going to the Brigham, not Children's, because she was worried that my sixfootfour frame might not fit in their beds.

I was about to be a very sick kid surrounded by very sick adults, 20, 30 and 40 years my senior. But what I remember most is sitting on the stone wall at the bottom of my driveway that evening, experiencing dusk, blossoming trees, the smell of spring arriving and terrified for probably the first time in my life. I was faced with a situation that probably, likely even, wouldn't work out.

My mind raced as I sat on that wall. It was only a couple of minutes I sat there waiting as my mom got my brothers ready for another neighbor, but I was alone and it was quiet. Then I got into Larry's Volvo with a sinking feeling I maybe probably wouldn't ever get back home.

We arrived at the hospital to a busy ER Friday night. Reception gave me a mask and latex gloves then quickly found a private room. Doctors streamed in and out. My dad got there. And that one word on the phone ‘leukemia’ got filled out in detail.

Philadelphia chromosome positive acute myelogenous leukemia, with a touch of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic myelogenous leukemia throne in just for good measure. Very poor survival rates.

I was numb and terrified but so tired I couldn't really process it. Something called the bone marrow transplant was the only treatment but it took time and luck to even make it to the transplant floor. I had to get through induction chemotherapy, potentially multiple rounds of maintenance chemo, not get sicker. We had to find a donor. My brothers? My mom was a twin so maybe my cousin? My parents? They all needed to get tested. But, first, I had to make it to Saturday.

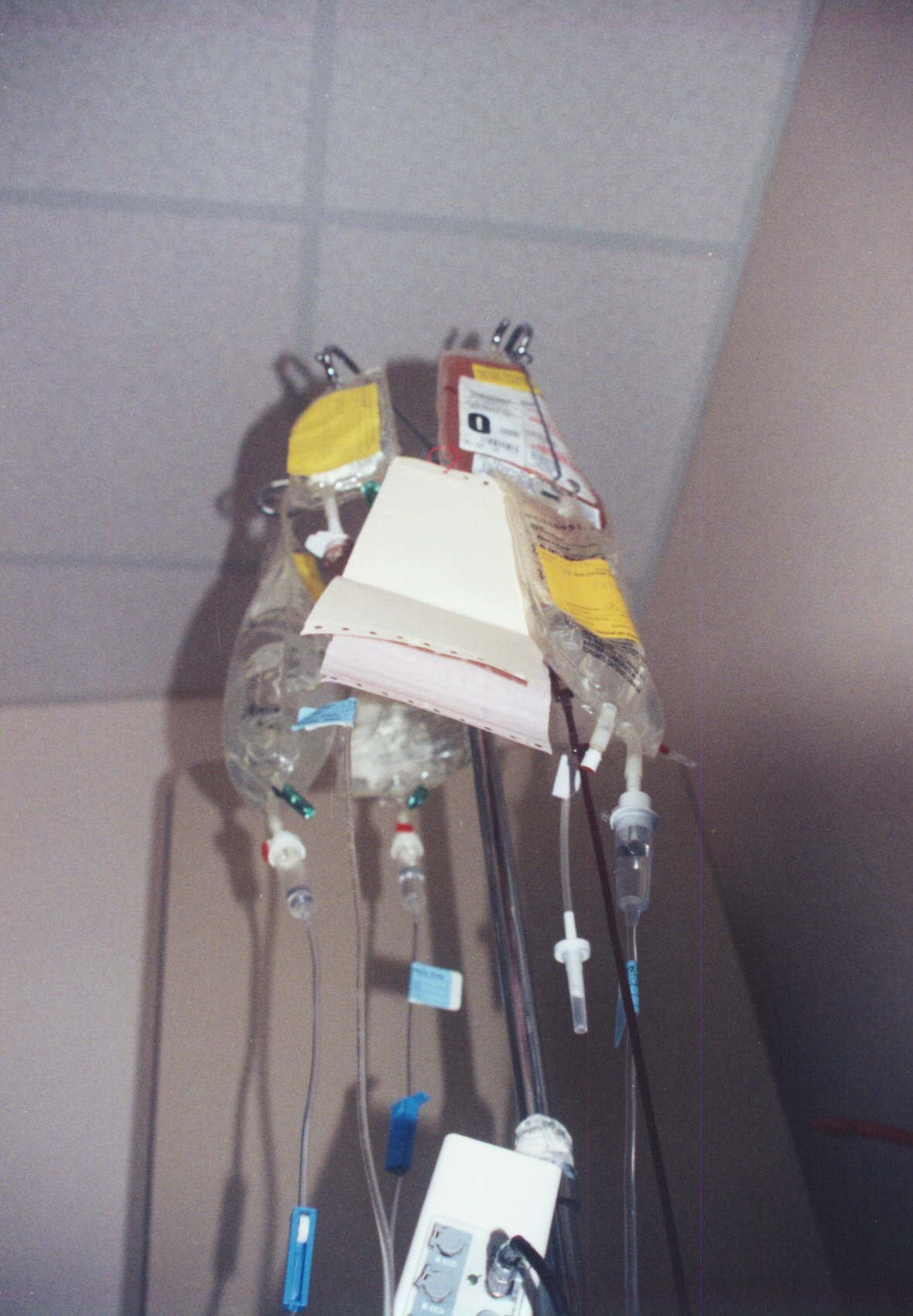

The doctors ran a leukapheresis machine in reverse all night just to pull immature blood cells out of me as fast as they could to keep me alive. Machines beeping all night, uncomfortable and alone.

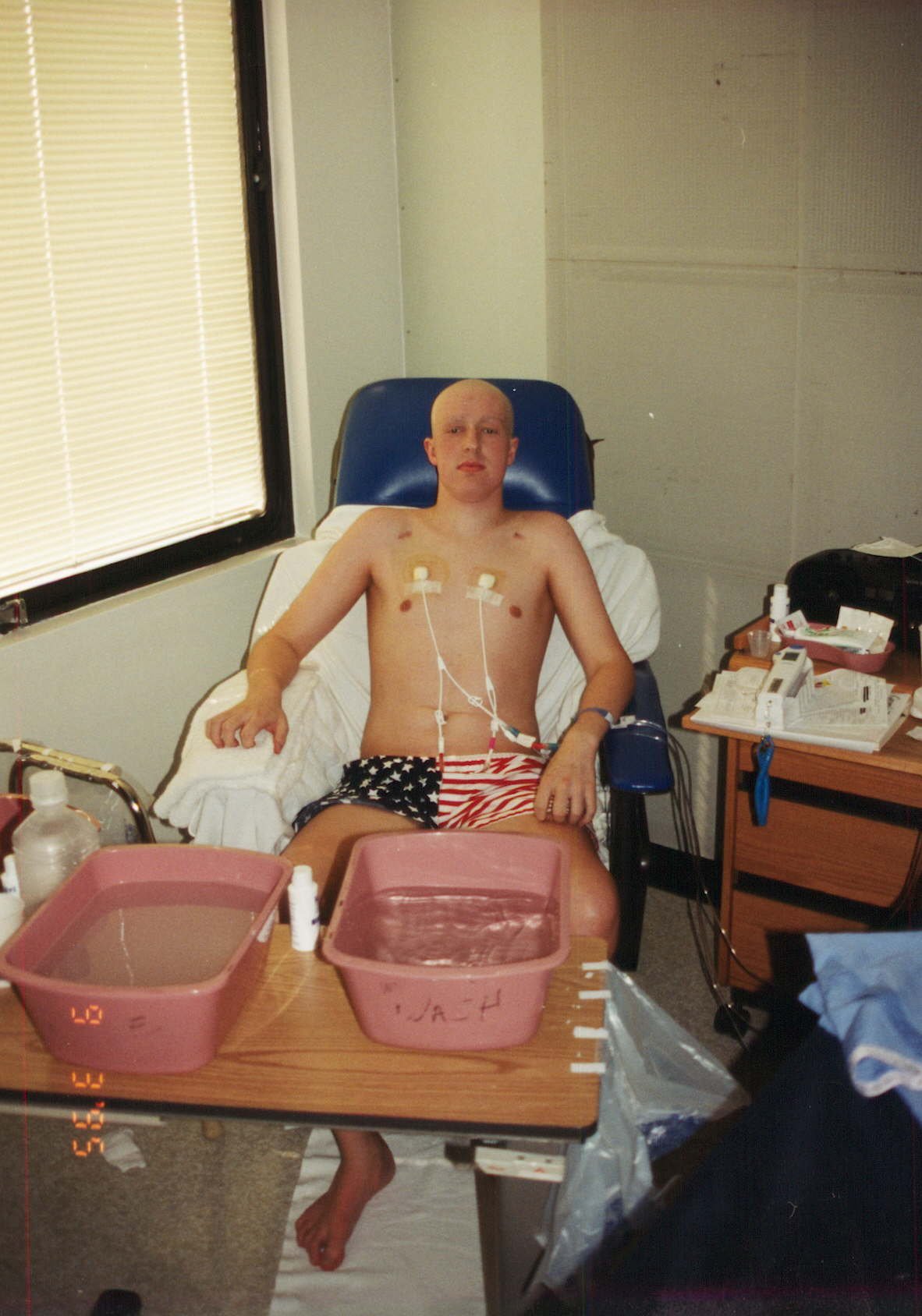

By 7:00 AM Saturday morning, I was in surgery getting a Hickman catheter put in. By lunch, I was starting chemo.

I was lucky to be living near one of the best teaching hospitals in the country, but that also meant many days I had flocks of interns and new residents coming through my room, working on their bedside manner, trying to decipher my initial symptoms to figure out what I had or just checking my vitals one after another.

I got to talk to them. I wasn't going anywhere and they were almost my age. Some in engineering degrees, some were physician scientists who did research, and all were excited to be taking care of people.

They talked about their college experiences and tried to take my mind off of the daytoday. One even spent weeks trying to convince me to apply to Harvard.

Time went fast yet slow and I learned to listen, pay attention and be grateful for each new morning.

I played Scrabble with my grandmother a lot. I watched Fawlty Towers with my dad almost every night. Ate all the junk food I could yet still lost 20 pounds.

The night of my prom, I ate a Whopper from the food court alone in my hospital room and I watched the Triple Decker across the street burn down. I lost all my hair, including eyelashes.

I studied for my final exam through chemo and couldn't remember anything I had studied. I walked endless loops around the floor.

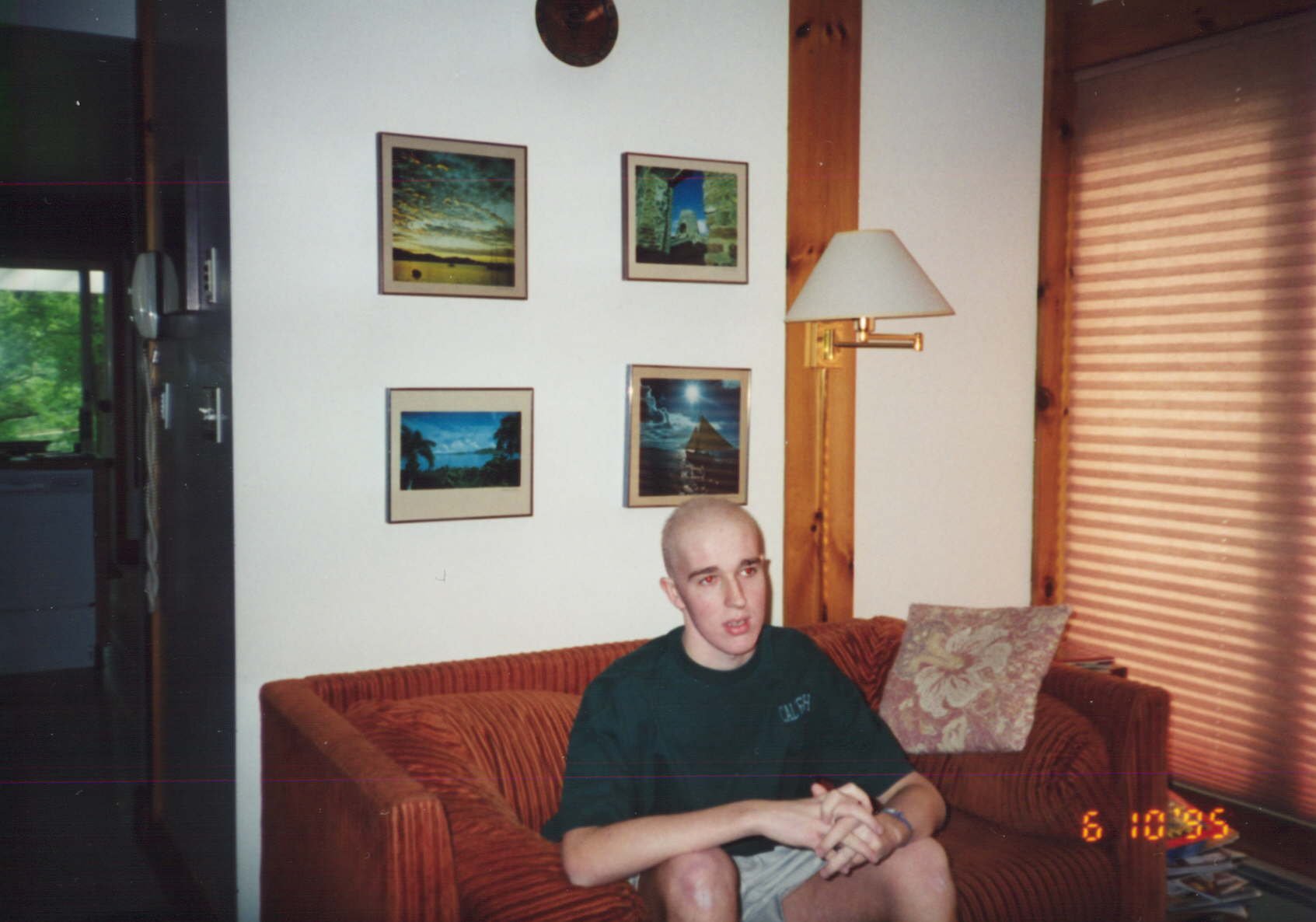

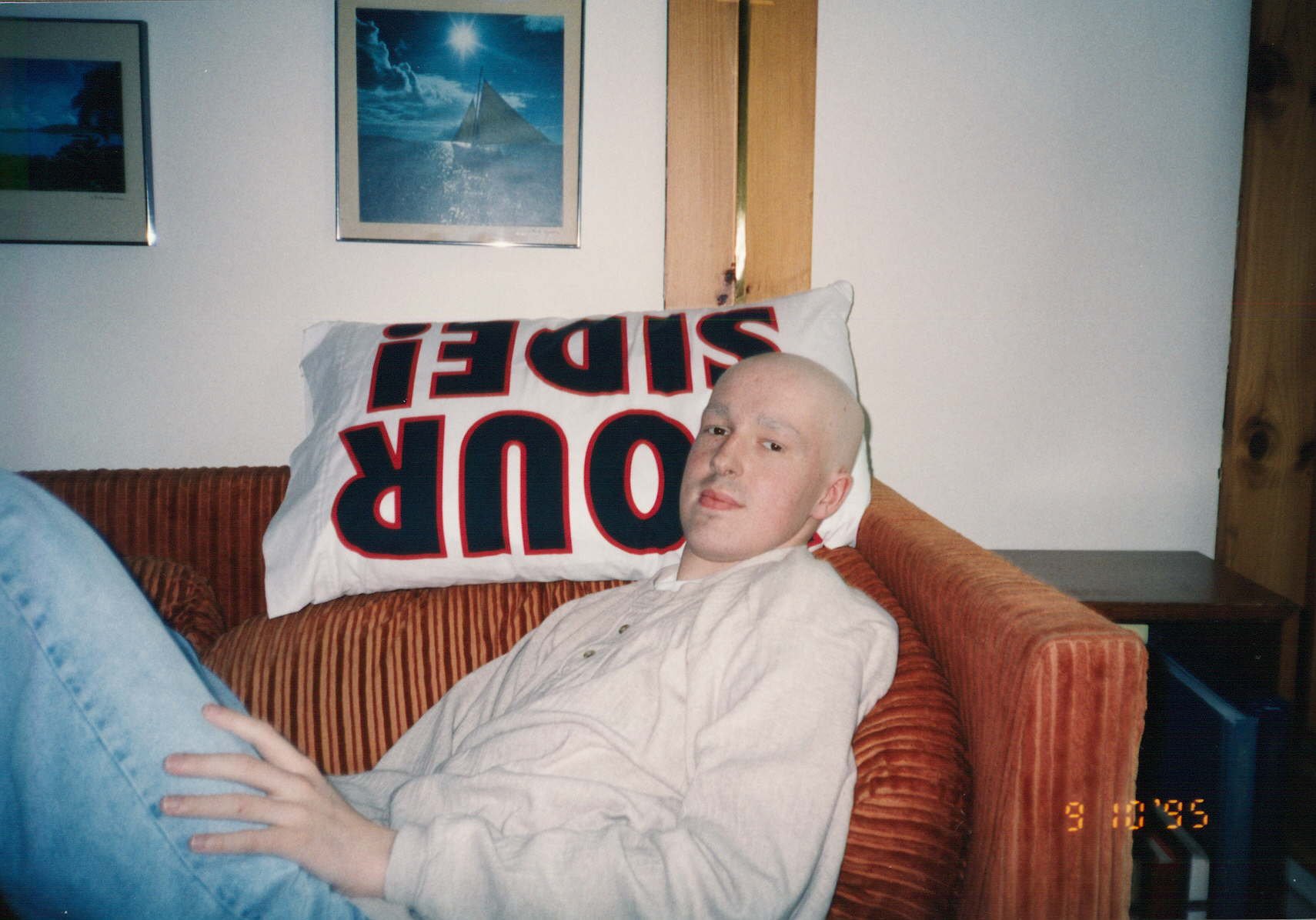

Then I went home from that concrete cityscape after induction chemo in June and remember being in awe of the trees. The trees that were just starting to come to life in the spring when I left were green and lush.

One of those first days back, I also learned my middle brother was a perfect marrow match. I now just had to make it to August for the transplant.

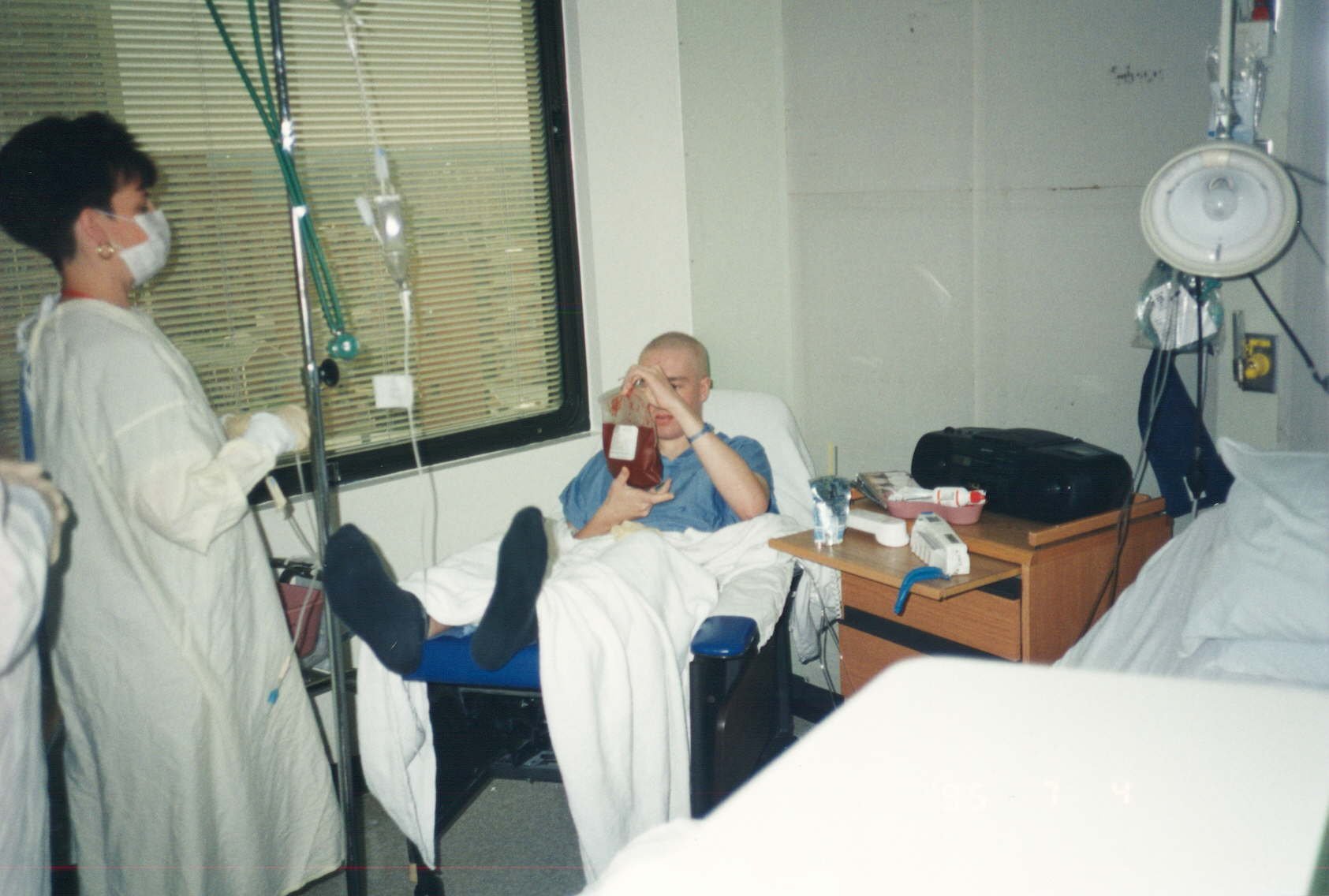

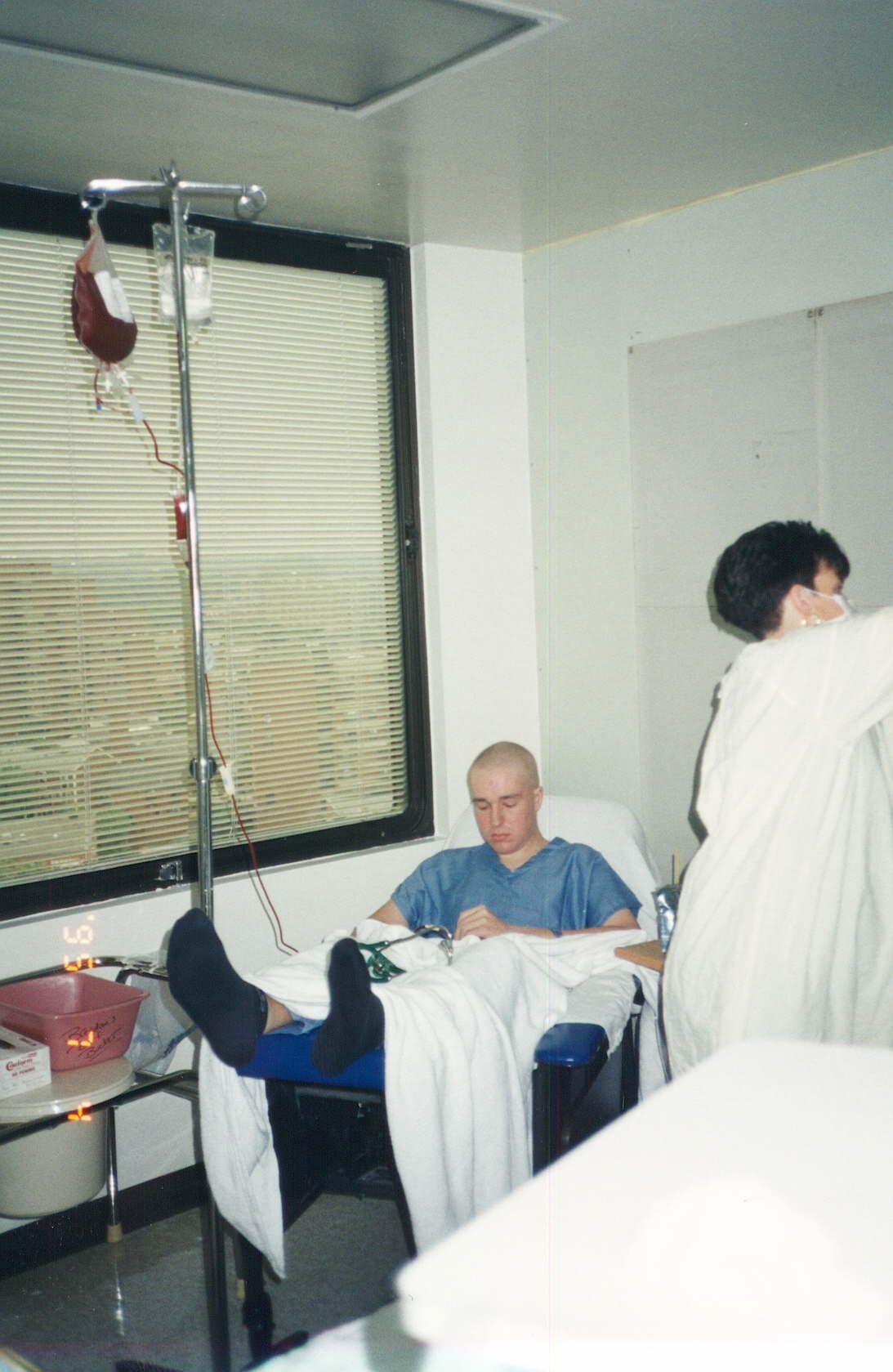

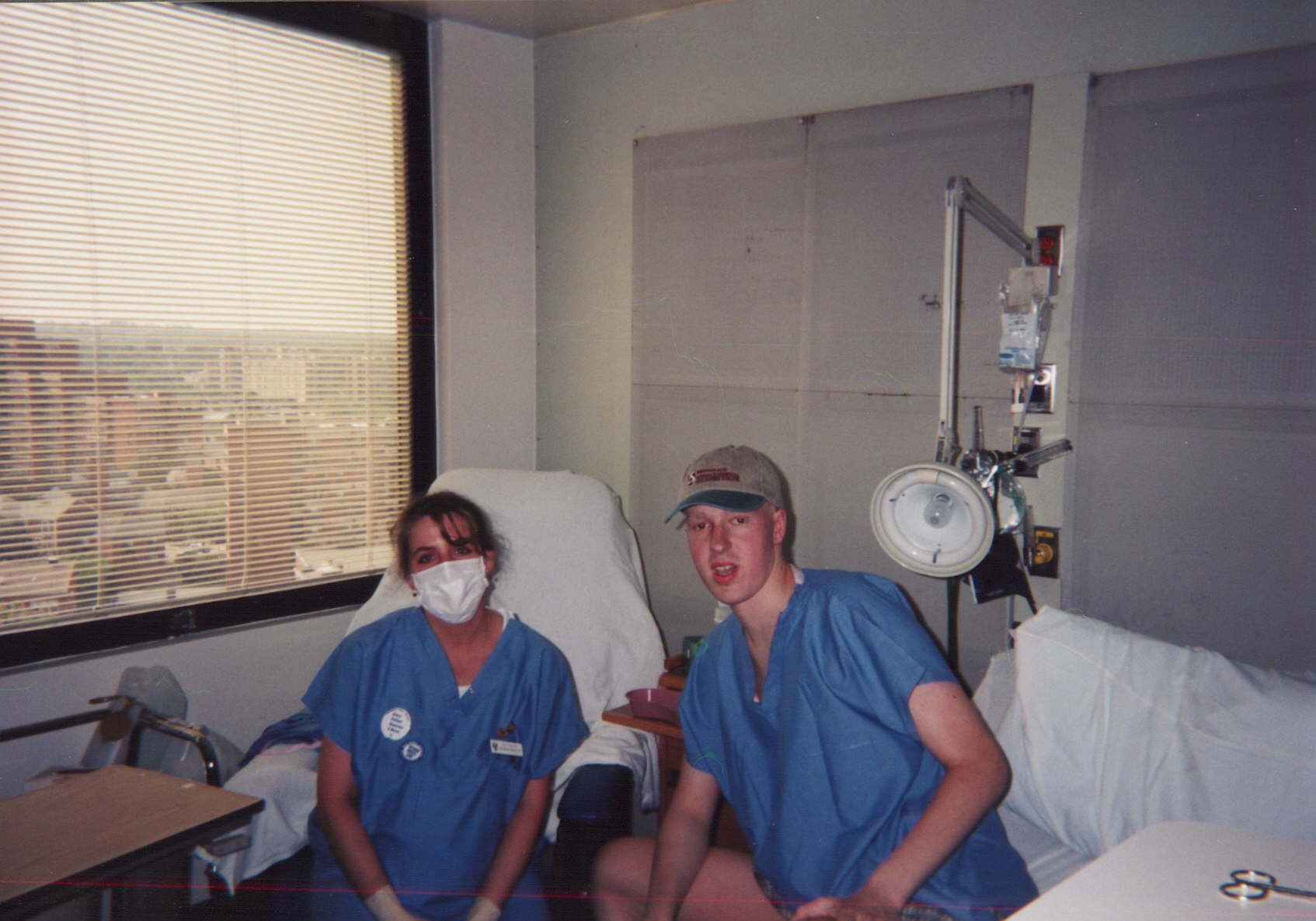

Stepping under the transplant floor, I met Michelle, my charge nurse. She was pregnant with her first kid and tasked with taking care of me. She was my one constant. She was about five feet tall. She felt like she was barely older than me and greeted me with a smile every morning.

Transplant was hard. The total body radiation and chemo I needed to get ready for the transplant was intense. I remember being bundled from my isolation room across the hospital to the radiation chamber twice a day. There was a colorful fivefoottall parrot painted on the wall of that leadlined concrete walls. For the kids, but all you could think about was how that parrot should have been dead a thousand times over from all the radiation it saw.

Lying alone in the silent chamber on a simple cot, I would hear a low whirr and feel every part of me getting cooked.

After a week, I was on hardcore pain meds and just a shell. I sat in silence and watched a bag of my brother's bone marrow dripped into my catheter. Then five weeks of hanging by a thread.

The bad nights are still burned into my memory. Temperature spiking, numbers crashing, everyone on edge and me just so, so tired.

I made it through those days with Michelle, but I couldn't help but notice rooms around me on the transplant floor where I saw that same burst of energy, then heard a code and went into silence and loss.

Getting off the bone marrow floor was a privileged few who stepped on God back then.

There's a point in the middle where I started thinking about my future. I just decided that either I was going to make it through, in which case I should have a plan, or I wouldn't. But, really, it was my community: nurses, doctors, my family and Michelle. They saw me, heard me and showed me compassion and that was empowering. It was the support I needed to dream about what was next.

Somewhere buried in all those interactions with doctors and nurses, I heard about the idea of tissue engineering. The ear mouse, actually. A group of engineers and doctors who grew human cartilage cells in the polymer structure on the back of the mouse in the shape of a human ear. I saw a way of blending engineering with taking care of people, a future.

Michelle and I made it out together. The morning I was discharged from the marrow floor, Michelle got me ready. I was heading home with no immune system, about to spend a year in isolation hoping to heal.

I didn't want to go home. How could I be safe?

We took a picture sitting on my hospital bed and then she bundled me off.

Michelle went home that day too and had her baby that night. She somehow willed herself to hold on so she could get me home.

Making it to a hundred days posttransplant was my goal, so I counted. One becomes ten, ten became a hundred, a hundred became a thousand, and I'm still counting. Later this year, a thousand becomes ten thousand days. 27 years, can you imagine.

I'm now a professor of chemical engineering at a Midwest public research university. I teach and I run a tissue engineering research lab. My students do exceptionally cool things, like straight out of Star Trek cool.

I also carry a weight with me. I feel it's my responsibility to make a difference in this world. For me, that includes making science bigger, more inclusive and more equitable. I want people to experience the joy of solving problems and having impact. I believe solutions to a lot of our problems come from communities that care for one another to make an exceptional future possible. And I know that starts with compassion.