In this week’s episode, both of our storytellers strive to be their authentic selves in academia.

Part 1: Raul Fernandez dreamed of going to university to study engineering. When he gets to Boston University, he feels unwelcome.

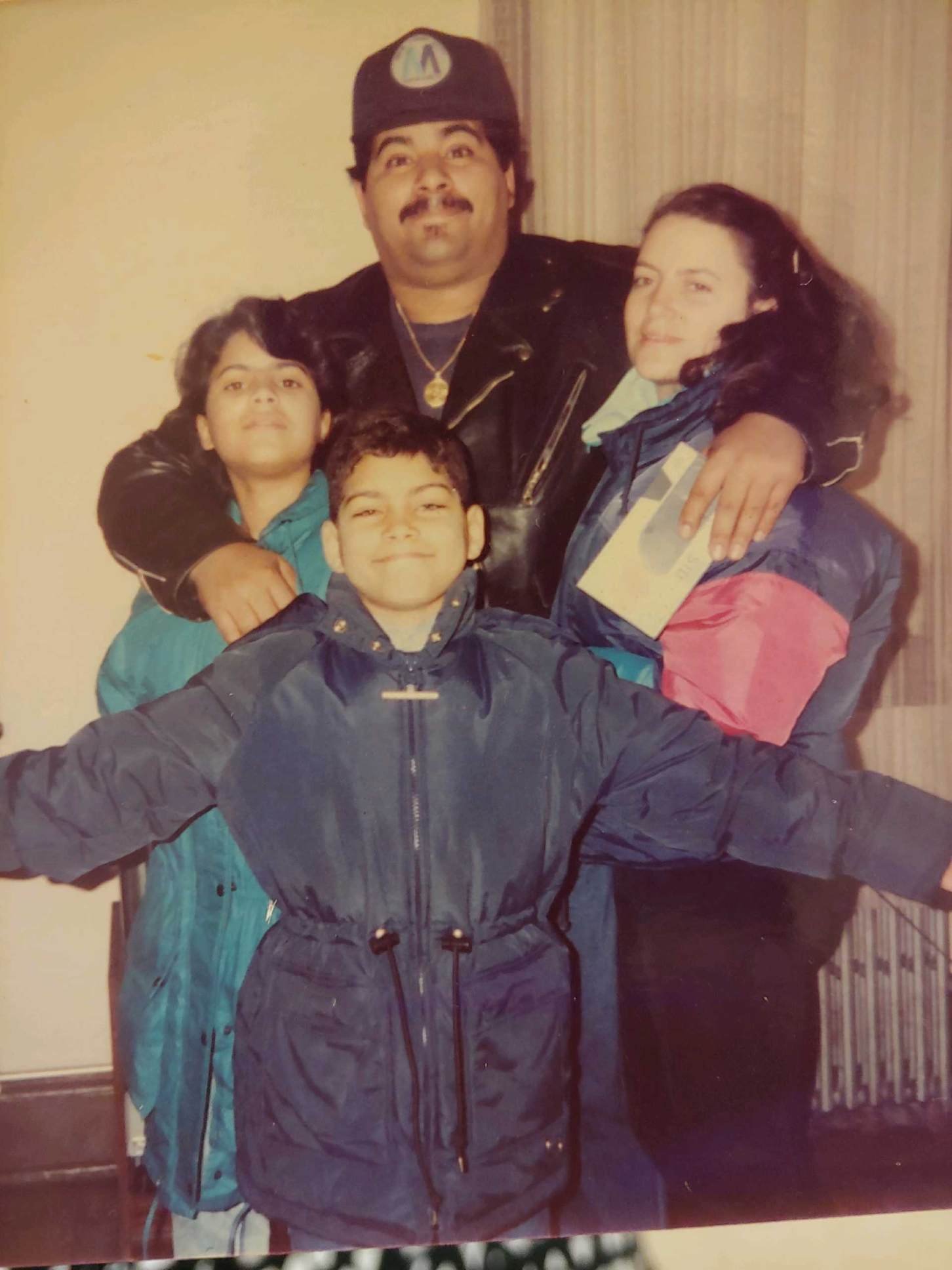

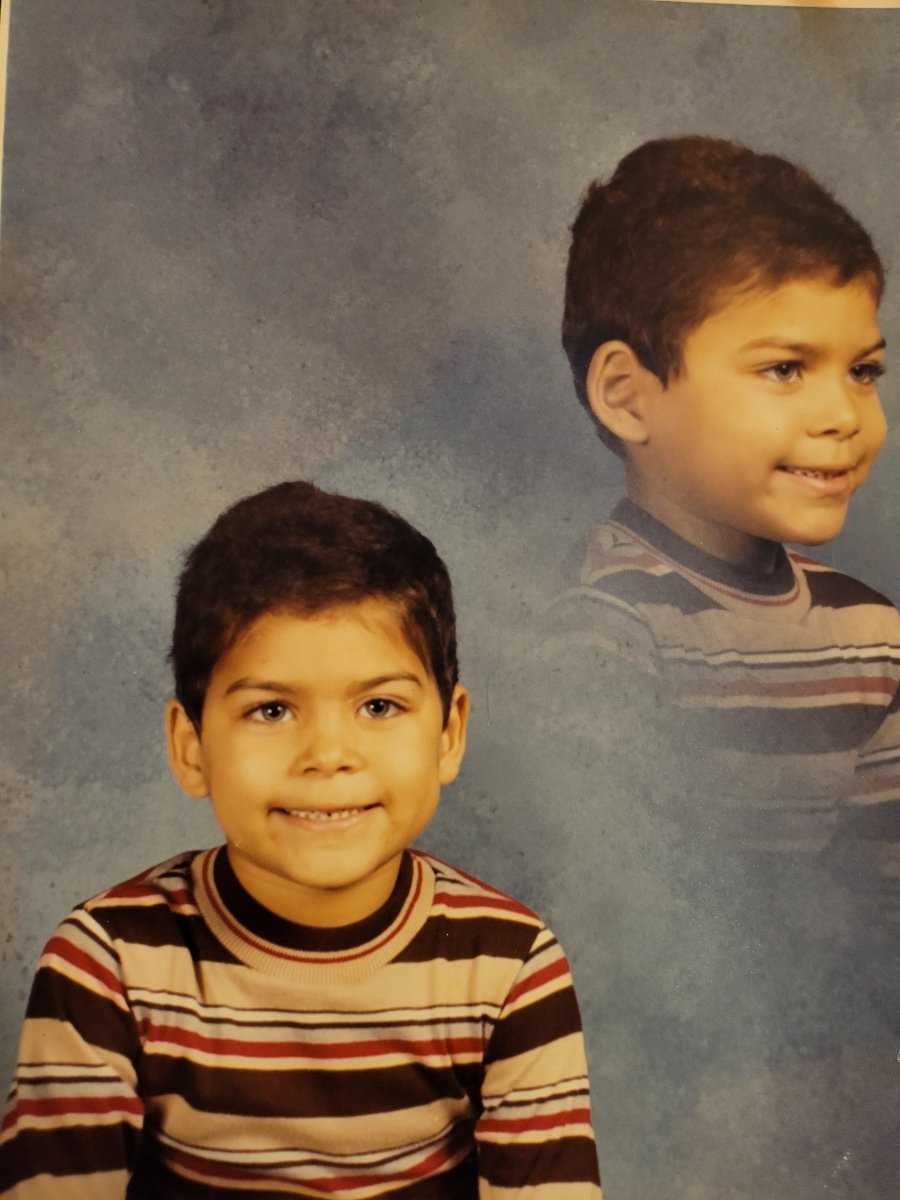

Dr. Raul Fernandez is a scholar-activist. As a Senior Lecturer at Boston University, he studies, writes, and teaches about inequities in education. As the Board Chair of Brookline for Racial Justice & Equity, he rallies his neighbors in the relentless pursuit of racial and economic justice. In the last few years alone, he researched and wrote a piece that helped topple a monument to white supremacy, created a film series that engaged thousands of participants in challenging dialogues, and trained thousands more in equitable policymaking at institutions in the US and abroad. Dr. Fernandez also served as a member of Brookline Select Board – the first Latinx person elected to that position. During his time there he created a working group to support public housing residents, a Racial Equity Advancement Fund, and a task force to reimagine public safety. He lives with his formidable partner Christina and their three kids in Brookline, and enjoys trips to "big park" and "tiny park" with his adorable toddler Maya.

Part 2: Cynthia Chapple was continually underestimated by her teachers and struggled with minimizing aspects of herself to be accepted.

Cynthia Chapple is an innovative scientist, an advocate for black girls and women, and champion of equity. In keeping with this work, she is founder of Black Girls Do STEM, an organization offering exploration of STEM career pathways through hands-on engaging curriculum in the areas of Science Technology, Engineering and Mathematics to middle and high school black girls to expose them to career pathways and empower them to become STEM professionals. Cynthia looks for more ways in which she can act as a conduit exposing young black girls to STEM industries and a diversity, equity and inclusion voice within the STEM workforce space to create welcoming policies, practices and cultures for Black people and women to thrive. As a Black woman in STEM this work is deeply personal and Cynthia draws upon her lived experiences as a result of her intersectional identities to offer ideas and solutions that truly foster belonging and give the opportunity for people to show up as their authentic selves. As a founder she sets strategic focus, foundational policies, practices and culture around the program design and student experience for Black Girls Do STEM. Subsequently she has launched CC Black Lab a research and manufacturing company of cosmetic products with the first brand being produced being Black Velvet SPA. Cynthia received her Bachelor of Chemistry Degree from Indiana University Purdue University at Indianapolis (IUPUI) and her Master of Science in Chemistry from Southern Illinois University Edwardsville (SIUE). She subsequently spent five and a half years as a Research and Development Chemist in the manufacturing industry. She has been a member of both the American Chemical Society and the Society of Cosmetic Chemist for over 5 years combined. Cynthia’s superpower is leveraging her expertise and power to dream on behalf of Black liberation.

Episode Transcript

Part 1

When I was a kid, I loved science, and I mean all of it. I'm talking about astronomy, chemistry, physics, computers, but engineering, engineering was my jam. The idea that you could build structures that last for hundreds of years, how cool is that. And, for me, I remember deeply that that is what I wanted to be. That was a big dream for me coming from where I come from.

Raul Fernandez shares his story at MIT Museum in Cambridge, MA in September 2023. Photo by Kate Flock.

I grew up in 1970s, ‘80s in El Barrio, Spanish Harlem in New York and later on in the South Bronx, an underpaid family in an under resourced community with typically under resourced schools. Certainly not the kind of schools that produce engineers. But I got a big break when I was just four years old.

There was a teacher, Ms. Freelander who had to decide who amongst the kids in her class she was going to recommend for this talented and gifted program. The stakes were high. You get in this program. You go on this really well resourced path. Success. If you don't, you're likely to stay in the typically under resourced schools and the communities that I lived in.

For me, by the time I was in high school, that would have meant going to Stevenson High School where, at the time, just 30% of the students were graduating. That's 3 in 10 students graduating high school, never mind going on to college to be engineers. So the stakes were high for me.

And because I got in that program, I ended up at Manhattan East and, later on, the Bronx High School of Science, two schools that really fostered in me this love of science and supported me throughout.

That's not to say it was easy. I mean, I was a smart kid but I was also a distracted kid with lots of problems going on at home and in my community. I had to really struggle to get through that time.

Also, my mind, like it's doing right now, used to wander a lot. I would sit sort of looking out the window while class was going on and just imagine Spider Man swinging from rooftop to rooftop.

I would also lose time a lot. You know what that is when you lose time? It's like in a movie, there's a time jump and some time has passed and you have no clue what's happened, what's been said. Imagine that in class when the bell rings. No clue what's going on. I had to find a way to quiet my mind a little bit.

I did that at home. I was able to actually listen to music, a little hip hop music. And when I was studying calculus, Biggie. Chemistry, Pac. Little East Coast, West Coast, right? It quieted my mind and allowed me to focus on what it was that I was doing. It's a little counter intuitive. The problem was, when you go into school, you can't take tests with music on, right?

Well, there was this one teacher. I don't remember his name, although I wish I did. He was this teacher of color, Latino maybe. Because we built the relationship, I felt comfortable enough asking, like, "Hey, this is how I study at home. Would you mind if I took my test with headphones on?" And he got it.

He did ask me if he could listen first to see if I'd recorded the answers to the test. He's not dumb.

Raul Fernandez shares his story at MIT Museum in Cambridge, MA in September 2023. Photo by Kate Flock.

It worked out and I felt supported in that way and supported enough to get to Boston University in the mid ‘90s as an undergraduate student, kind of. I got the acceptance letter. I'd applied to the College of Engineering, of course, and was very excited when that acceptance letter came, except it didn't say College of Engineering.

It said, "Congratulations. You've been accepted to the Science and Engineering Program." That was a surprise to me because I'd never applied to it. What was it?

Well, as it explained in the letter, it was a bridge program. You get into this program, you do well enough for two years, and then we'll bump you up to the College of Engineering and you can be a proper engineer at that point.

Okay, I'll do it. Sure. Sounds good to me.

I learned a little bit more about this program. I realized it was a bridge program. Unfortunately, this bridge program, instead of focusing on the strengths and abilities of the kids there, really focused on our weaknesses. I also realized during the first day, when I was kind of excited, maybe a little nervous, and I looked to the left and right at me and I was like, "There's a lot of black and Latino kids in this program. Why is that?"

Boston University at the time, still, it's a very white institution. I remember going on my campus tour with my mother and the tour guide was really excited to tell us that the previous year, Boston University had won a national championship.

I was like, "Yeah?"

And then he said, "In hockey."

And I was like, "Oh, boy. This place is white."

Still, I was still excited to be there. Of course, I felt like I didn't belong. I felt out of place. No question about that. And this program, knowing that it put these black and brown kids in this program that was different from large university, different from the college, made me secure in the fact that I was out of place there.

Not only that, it moved too fast. It may seem like all STEM fields are designed to weed you out, but this was supposed to be a bridge for you to move forward. It felt like there were a lot of hurdles in our place. It moved so fast that my classmates and I would actually take turns asking questions.

“Can you get this one? I got the next one.” I'll raise my hand next time, right?

And the professors more often than not would say, "Sorry, we've got to move on. There's just not enough time. We have to move on."

And if that wasn't enough, there were no black or Latino professors there as well. We really felt like they weren't making an attempt to get to know us personally. We were struggling academically, sure, but we had all these other needs, too, that weren't being met.

So, we relied on each other. But we were all struggling, so we could only help each other so much. It was frustrating. It was demoralizing. It was demeaning. This is a thing that I was good at, that I was passionate about, that I knew was my future and I was failing miserably at it.

I remember sitting in my dorm room and I was doing some chemistry work and that feeling came up, that frustration. The kind of frustration that starts to turn to anger at some point. I remember thinking, “Man, life sucks. This program sucks. I'm so mad. Everything's wrong. Nothing's going right for me.”

Before I knew it, I was standing up with my $250 chemistry book in my hand and I hurled it across the room, except it was a dorm room so it landed right there. But you could feel palpably. I could. Certainly, my anger in the moment , and it made me realize something had to change.

I was looking for a bright spot and I found one. Of all the classes that I was taking, the one that I was doing the best in was actually an English class . loved it. I was thriving. I used to write rhymes when I was younger so putting pen back to paper felt good. It felt natural. It felt like it was what I was supposed to be doing.

When I talked to some friends, I realized that there was this college called the College of Communication and I was so excited to see all the coursework they had there. I said, “I have to be in this college. I have to be in there. What do I need to do?”

Well, you've got to get the signature of the director of your current program to switch to the next program. Bet. No problem.

So, next day, I go into the director of the Science and Engineering Programs Office. His name is Chip. I laid it on pretty thick because I wanted a signature.

I said, “Hey, you know, this program has been amazing. So supportive. My friends rave about it. However, I found this thing that I really love. It is my new passion. I need to follow it. And the only thing I need from you, Chip, I just need a signature on this this paper.”

Chip looks at the paper, he looks at me, and he says, "No."

No? Can he even say no? This is my life. This is my future. I'm paying to be here. Like how is this person telling me no?

I'm in shock. I'm confused. Am I going to have to stay in this program and have to leave BU? I don't know.

Raul Fernandez shares his story at MIT Museum in Cambridge, MA in September 2023. Photo by Kate Flock.

Before I could say anything, Chip follows up. Chip, a man with a punchable name and a face to match. Chip tells me, “We don't like students coming in the back door and then doing whatever they want when they get here.”

Oh, Chip.

Now, again, this frustration, this anxiety, it all turns to anger. And I unleashed a slew of expletives on Chip that are not fit for the stage. But I will tell you, it was punctuated by this. “Do you really want a fucking kid like me in your stupid fucking program, Chip?”

Chip looks at me and he says, "No, I most certainly do not." And he signs the paper right there.

Thanks, Chip.

I walked out of there feeling a little bit excited, worried about whether or not I was going to get in trouble for what I just did, but also this sense of calm that came over me. I didn't really know what was going to be going on next, but I knew whatever happened it was going to be on my terms.

Thanks.

Part 2

Today, I call myself the Chief Black Girl Doing STEM. I'm not quite sure what all that means, but I would like to take you on the journey of self discovery.

My science story starts in fourth grade in Mr. Estes's class in Chicago Public Schools. See, I'm a Chicago South Side. And as early as I can remember, walking out into the big city, I was curious. Asking questions, looking around, interacting with the things around me, wanting to understand how everything worked.

Cynthia Chapple shares her story at Public Media Commons in St. Louis, MO in April 2023. Photo by Michael Thomas.

Mr. Estes was an African American male educator. He was young and he was cute and he smelled good, so fourth grade me was smitten. I can recall being in fourth grade, and Mr. Estes would have these math competitions where he would stick out his hand and it would be you versus your opponent, and it was whoever hit his hand first got to answer the math problem. I not only wanted to be the winner because I was competitive, but I also wanted to touch Mr. Estes's hand.

That was the first time where I was affirmed as being good at math, as being a problem solver. But not only just math and problem solving but, really, an ability to figure anything out. That was pretty much the extent of my K 8 experience and I would end eighth grade as class valedictorian as a result.

I started high school, also in Chicago Public Schools. I transferred to Indiana because I moved with my sister to attend Lafayette School Corporation. In high school, I was in an IB program, taking advanced math. When I went to school in Indiana, somehow, I ended up in the lowest class possible, landing in a remedial pre algebra course. I know it was remedial because on the block schedule, instead of going every other day, I went every day.

I remember going to talk to the counselor and explaining that I needed to be in different classes and asking why wasn't I put into comparable coursework compared to what I was doing in Chicago. She explained to me that they weren't going to accept any of my Chicago credits, that they couldn't certify that program.

I was like, “Isn't IB an international distinction?”

That was my first instance of feeling underestimated. Of somehow feeling as though I was seen as a black girl from Chicago Public Schools and then assumed the worst, that somehow I just needed to go into the lowest coursework possible.

I ended up graduating high school on time with honors, after also working to get all of the credits that they did not give me back from Chicago, because that's how easy high school was. Just a low brag.

I attended undergrad at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis. I say IUPUI. I was a forensic science chemistry double major, content on finishing a five year degree in four years because I had a first generation scholarship.

I can recall taking about 50% coursework in criminal justice and 50% of my coursework in science. I was in a forensic presentation course and my professor was an ex prosecutor. Forensic presentation was all about forensic history, case studies and giving comprehensive speeches.

I put in my first paper and gave my first speech and I remember getting the notes back and it was just riddled in red ink with a big fat F.

My professor said to me, "Your speech was terrible and you write how you speak and I'm afraid that you're just not gonna come off credible if you do not improve your diction."

Cynthia Chapple shares her story at Public Media Commons in St. Louis, MO in April 2023. Photo by Michael Thomas.

I was there again, right there in a moment of feeling underestimated.

I can recall that semester wanting to shrink. I went from being the student that sat in the front of the room raising my hand to ask big questions to sitting in the back, trying to shrink and just become invisible. I spent two to three days a week in the communications lab practicing my presentations, trying my best to sound how what I thought was credible, which was basically not black. Two to three times in the writing lab trying to, as my professor had stated, not write how I spoke.

So, I got to the end of the semester and I'm sitting in the science student lab and there's these huge glass doors that go from the floor up to the ceiling. The professor is walking by and he sees me and he proceeds to come in. For a moment, my heart stops.

He opens the door and he says to me, "Cynthia, I wanna tell you that you're the most improved student of the semester. That after that first paper, you really turned it around, and maybe you're gonna make an awesome scientist after all."

In that next moment, all I felt was triumphed because, yes, I had won and I had shown him that I could be a scientist. That I could be a credible witness and that I, in fact, belonged in science.

But that triumph lasted only a moment and I can recall my entire body going hot and deep sadness coming over me. And in that next moment, I sat with a feeling of self betrayal. I questioned had I given up too much of me of how I spoke, of how I carried myself, abandoned all of my purple color for stale black suits? Sure, there was this person who now thought I was going to be a great scientist, but at what cost?

Then I asked myself, “Is science always going to ask this of me? Ask me to melt and mold into something that I am not?”

Brené Brown says that belonging does not ask you to fit in. That fitting in is when you scan a room and adopt the ideas, the posture, the behavior, and language of others until you render yourself invisible.

That semester I had decided to fit in, because my difference, my identity, the things that had made me me were called out so loudly and so negatively.

Cynthia Chapple shares her story at Public Media Commons in St. Louis, MO in April 2023. Photo by Michael Thomas.

I've had the opportunity to present at global innovation conferences with scientists from Germany and Italy and other places in the world. I started those presentations letting the audience know that my favorite color is purple, that I love chocolate, and that my first language is African American vernacular English, i.e. Ebonics. The presentations went off without a hitch because, I assure you, in global rooms, perfect English is not the standard.

I have stood on manufacturing engineering floors with my silk toe shoes and my blood caps, and I have made sure that my lip gloss was always popping, bringing my whole self. Today, there is no self betrayal. I have products that you can walk into the store and buy off the shelf, products that you use in your devices, the things you use every day in your cars and in your homes that I made.

I am sure that I am science, because every day I get up and I walk out and I observe and I question and I have the courage and the curiosity to see what does not yet exist. That's something deep inside me. As much as I am sure I am science, I was then, I am now and I will forever be, as Barack Obama so affectionately refers to Michelle LaVaughn Robinson, a girl from the South Side.