In this week’s episode, both of our storytellers find themselves reckoning with the choices they’ve made—discovering how a single decision, whether made years ago or in the chaos of a crisis, can shape who we become and the responsibilities we carry.

Part 1: When Misha Gajewski’s grandfather has a stroke while the rest of her family is out of town, she suddenly becomes the emergency contact.

Misha Gajewski is the artistic director and host of The Story Collider podcast. She is also a freelance journalist, educator, and copywriter. Her work has appeared on Vice, Forbes, blogTO, CTV News, and BBC, among others. She’s the co-found of the world’s first 24-hour True Storytelling Festival and a proud cat mom. She has also written scripts for the award-winning YouTube channel SciShow.

Part 2: After learning that her mother gave up on her dream of becoming a musician, Paula Croxson vows never to give up on her dream of being a scientist.

Dr. Paula Croxson is a neuroscientist, award-winning science communicator and storyteller. She is a Senior Producer at The Story Collider and the President of the Board of Directors. In her day job, she is President at Stellate Communications where she supports academic and nonprofit science communication. Paula has an M.A. from the University of Cambridge and a M.Sc. and a Ph.D. from the University of Oxford. She was an Assistant Professor of Neuroscience and Psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai for 5 years before shifting her career focus to science communication and public engagement with science, first at Columbia University and then at the Dana Foundation. She is passionate about communicating science in meaningful and effective ways, and fostering diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility in science. She is also a musician, playing flute in several rock bands, and a long-distance open water swimmer. The swimming is apparently for “fun”. You can learn more about her at paulacroxson.com.

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

PART 1

I'm seven years old and I'm sitting at my grandparents' dining table. I can feel the plastic tablecloth under my hands. I can see the lake glinting in the sunlight in the distance. I can see my grandfather's face and I have this sinking feeling in my stomach, because I'm definitely in trouble.

He's like, “You ruined the desk.” and

I'm like, “Hmm, yes.”

Last night when I was supposed to be sleeping, I created an entire play universe with the office supplies on the teak desk, and Mr. Scissors had a prominent role as a figure skater. He did pirouettes and jumps and Lutzes across this beautiful teak desk leaving many, many, many scratches. And so my grandfather is looking at me with his stern eyes and he's like, “I'm going to have to refinish the desk. It's going to cost a lot of money. You ruined it.”

I feel bad because I didn't know. I mean, I was in my play universe with Mr. Scissors. It was a great time.

Misha Gajewski shares her story at Burdock Music Hall in Toronto, ON in October 2024. Photo by Glenn Pritchard.

And so I say the only thing a child can say in that situation, those magical words that absolve you of all your childhood sins. I say, “I'm sorry.”

He looks at me and he's like, “Sorry is not good enough.”

Now, that's like a super harsh thing to say to a child. Granted, I see that now. But what you need to understand about my grandfather is that he grew up in World War II, Germany. He was an Olympic level athlete, gymnast to be specific. So to say he was strict and rigid might be like the understatement of the century.

That's not to say he wasn't a loving grandfather, because he very much was. He would teach me how to do handstands in his front yard by telling me to like, plant my hands, suck in my stomach, stick it. I would inevitably tumble out and he would laugh and then pop up into his own flawless handstand.

He would teach me German words by getting me to guess the colors of the Smarties concealed in his hands. And when I was learning to ski, he would take me down every single run between his legs going over every single jump I demanded, probably ruining his lower back forever.

But the thing about my grandfather was like if you made a mistake, you knew you made a mistake. And it wasn't that he was a big, scary grandfather. He was just German, so he was terrifying. That made it really hard to be close with him despite the fact that we went on a family vacation every single year. Some people have friends as grandparents. I have acquaintances as grandparents.

It got even harder to kind of be close to him in 2018. He got diagnosed with Alzheimer's and vascular dementia, which is a type of dementia where blood clots restrict the blood flow that goes to the brain. I watched my grandfather become less and less of the man he used to be.

Misha Gajewski shares her story at Burdock in Toronto, ON in October 2024. Photo by Glenn Pritchard.

Probably the biggest thing I noticed were the physical changes. First, he would shuffle when he walked and then he couldn't really make it up the three little steps at my parents' house. Then he was like grasping onto railings or the person next to him just to make it like a few steps. And this was a man who used to be able to balance upside down on a four inch‑wide beam. He couldn't even balance on flat ground anymore. It was so cruel and so hard to watch this disease steal who he was.

And it stole his joy. He used to be the life of parties. He was always shouting and joking and laughing. At dinner parties now, he didn't even speak because the words weren't there. The man who always said, “Keep smiling,” didn't smile anymore.

One day in 2019, I get a phone call. It's from an unknown number and I answer it, which I know is weird as a millennial. On the other end of the line is a nurse from my grandfather’s nursing home.

She's like, “Hi, is this Misha?”

I'm like, “Yeah.”

She's like, “Your grandfather had a stroke and he's been taken to the hospital.”

My first thought is, why are you calling me? There are like four other adultier adults in this lineup before we get to me. I shouldn't even be on the page.

And then I'm like, “Oh, no, I'm the only one here.”

My parents are on a holiday in Scotland, like middle of nowhere, Scotland, and my aunt lives all the way in Calgary. So I'm it. I'm the emergency contact now. And I am so not ready to be the emergency contact right now.

I'm like, “Which hospital?” She tells me a name and then hangs up, and I'm like, “Great.”

I spend the next couple of hours calling the hospital, trying to get through to the nurse charge station, be like, “Hey, is my grandfather named Eric there?” Which seems so weird to call my opa by his first name.

And they're like, “Who are you?” And

I'm like, “Great question.” And I spend the next eight hours learning that he's maybe being moved to another hospital, but we're not sure.

And then I call that hospital. I'm like, “Is he there?” And they're like, “No.”

I'm like back at the other hospital. They're like, “Don't come. He's getting moved soon.” And I'm like, “Why?”

Then they're just busy because it's a hospital, so they don't care about me. And I'm like, “Cool, great.”

After like eight hours of playing telephone tag, I finally pin down a nurse. I'm like, “Hi, can you just tell me what's up? Like, was it a new stroke? How bad was it? Is he going to recover? Can he understand anything? Give me some details.”

She's like, “Yes, it was a new stroke. No, he's not going to recover. No, he's not okay. We don't know if he can understand anything, but the language part of his brain is still there.”

And I'm like, “Umm, yeah, the Alzheimer's and dementia probably took that, though, so, okay. What do I do? Do I come now?”

She's like, “Come tomorrow and the doctor will speak to you during rounds.”

And I'm like, “Okay, got it.”

The next day, I go to the hospital and I brace myself before I walk into the room. I walk in and I see my grandfather lying there. He looks so small and so frail. He's in the hospital gown and he's clutching the blue hospital sheets, shaking. I don't really know what to do.

So I go down and I sit next to him and I grab his hand. I'm not really sure what to say to him. I don't even know if he can hear me. I don't even know if he knows I'm there. And

Then I'm like, “Maybe I'll read to him.”

I'm about to pull out a book and start reading to him when the doctor walks in. He's this middle‑aged guy. He's wearing scrubs and the white coat and everything. He has kind eyes and he's like, “Hi.”

I'm like, “Hi, I'm Eric's granddaughter.”

He's like, “Great. How much do you know?”

I'm like, “Honestly, not much.”

He's like, “Okay.” And in an almost joking tone, he starts this spiel like he's given it thousands of times. He's like, “Okay, so there are two camps, Camp A and Camp B.”

I'm like, “Great.”

“Camp A is where we would put a feeding tube down your grandfather's throat. We'd basically force feed him but we'll keep him alive. There's not really a lot of quality of life there. That's Camp A, Option A.”

I'm like, “Um‑hmm.” My grandfather is holding my hand real hard now. I'm like, those are the hands that could hold his weight on the rings.

I'm looking at the doctor and I'm like, “Okay, what's Camp B?”

He's like, “Camp B is where we'll take him off fluids, he'll slowly dehydrate and his kidneys will fail, and he'll pass away peacefully.”

He's looking at me kind of expectantly. Like, I have to now, right now, decide which camp we're in.

My grandfather moans like he wants to say something, but I don't know if that's it. The doctor seems very unaffected by the moaning and the gurgling and all of the things that are happening. He just keeps looking at me. It doesn't seem like a Phone‑a‑Friend kind of situation, mostly because my mom is in the middle of nowhere Scotland and my aunt is in Calgary, and he looks like he needs a decision, like right in this moment.

And I've been in enough conversations with my mom and my aunt that I know they signed a DNR. We definitely don't want to prolong the suffering, so I'm like, “I think we're in Camp B, definitely Camp B.”

And he's like, “Okay.”

And before I can ask any more questions or say anything else, his pager goes off. He looks at me and he's like, “Do you need to get that?”

I look at him, I'm like, “Do you need to get that?”

He laughs, realizing I don't live in the ‘80s, and kind of is like, “Yeah, I do,” and leaves the room.

I'm like, “Cool.” And I'm just left holding my grandfather’s hand in shock that I'm the one who just made that call. I'm the one who chose if he lived or died. It shouldn’t have been me. Literally anyone else older than me should have made that call, but I don't know what to do. He's just gripping my hand so hard that I'm losing circulation in my fingers.

Misha Gajewski shares her story at Burdock in Toronto, ON in October 2024. Photo by Glenn Pritchard.

It takes about a week for my grandfather to pass. I don't really remember much about that time. My aunt came. We rubbed a lot of essential oils underneath our nose because the smell of hospitals is disgusting, and it sucked. But in the months after he passed, I kept having these dreams, these dreams where he was angry with me, like so mad. I really tried to just chalk it up to eating too much cheese before bedtime, but it wasn't going away.

One day, I'm in the car, and I'm driving to my boyfriend's place in London, Ontario. I'm like, “Okay, we got to make this right. We got to fix this.”

I don't normally commune with the dead. It's not really one of the things I do. I'm also not a super spiritual person. I don't even know if I really believe in the afterlife, but I don't really know what else to do. So I'm going to talk to him.

In my car, I'm like, “Opa, I'm sorry. I'm so, so sorry. I'm so fucking sorry. I know it shouldn't have been me who made that call. It should have been Mom or Vita or literally, like, not me, just not me.

And I'm sorry. I didn't know what to do, but I tried to do the right thing, okay? I tried to choose what you would have probably wanted. I know you didn't want to be a vegetable on a feeding tube. You hated people like that. You never wanted to see yourself like that. So I tried to make the right decision.

And I'm sorry. I had the conversation in front of you, but the doctor was there and I didn't really know what else to do. Okay? I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry.”

I'm bawling and begging into the silence of my car and this sense of peace washes over me. Again, not spiritual, but I think maybe he understands and he might forgive me. And maybe, just this once, sorry was enough.

Thank you.

PART 2

I first realized my mom was a human. Okay, just to clarify, I knew she was human. But when I was a kid, she was there for me and my sister in all kinds of ways that made her being centered around mine. So she would pick us up and drive us places in her beat up little Citroen 2CV. She would accompany us on the piano when my sister played cello, when I played the flute. And she kept a notebook with the names of my friends in it. And if they wronged me, she would cross them off. She was keeping tabs.

Paula Croxson shares her story at QED Astoria in Queens, NY in May 2025. Photo by Zhen Qin.

The first time I got my period, she knew, somehow, before I told her about it, and was ready with supplies and a letter excusing me from being late from school. So she was there in kind of this role of being there for me.

But when I was in my teens, I started to realize that she was a person in her own right. The first time that I realized that was when I first saw her cry.

I walk into the kitchen and she's sitting at the surprisingly 1970s beige melamine countertop. She has her arms on there. She looks like me. She's slim, athletic looking. But unlike me, she always has a great tan because she loves to be outside. This time, she has her head in her hands on the countertop and she's just sobbing.

I know why she's crying. Her mother, my grandmother, has been diagnosed with dementia, probably Alzheimer’s and it's getting much, much worse. They're going to have to sell her house and put her into care and use the money from the house sale to pay for that. It feels very final and serious and not what my grandmother would want at all, but there is no choice.

So I know why she's crying and I also know there's nothing that I can do except to give her the one thing I have, which is to go and put my arms around her and give her a hug. And so I do.

After that, I see it everywhere. I see the person that my mom is. I see her when she's being silly and joking around. I see her when I come home after school and she's listening to a piece of really emotional music, and she's just in floods of tears of joy at how beautiful it is.

And we start to talk. We start to talk as adults, almost, as women. I start to get this look into who she is as a person as I'm coming up to the age where I would go to college.

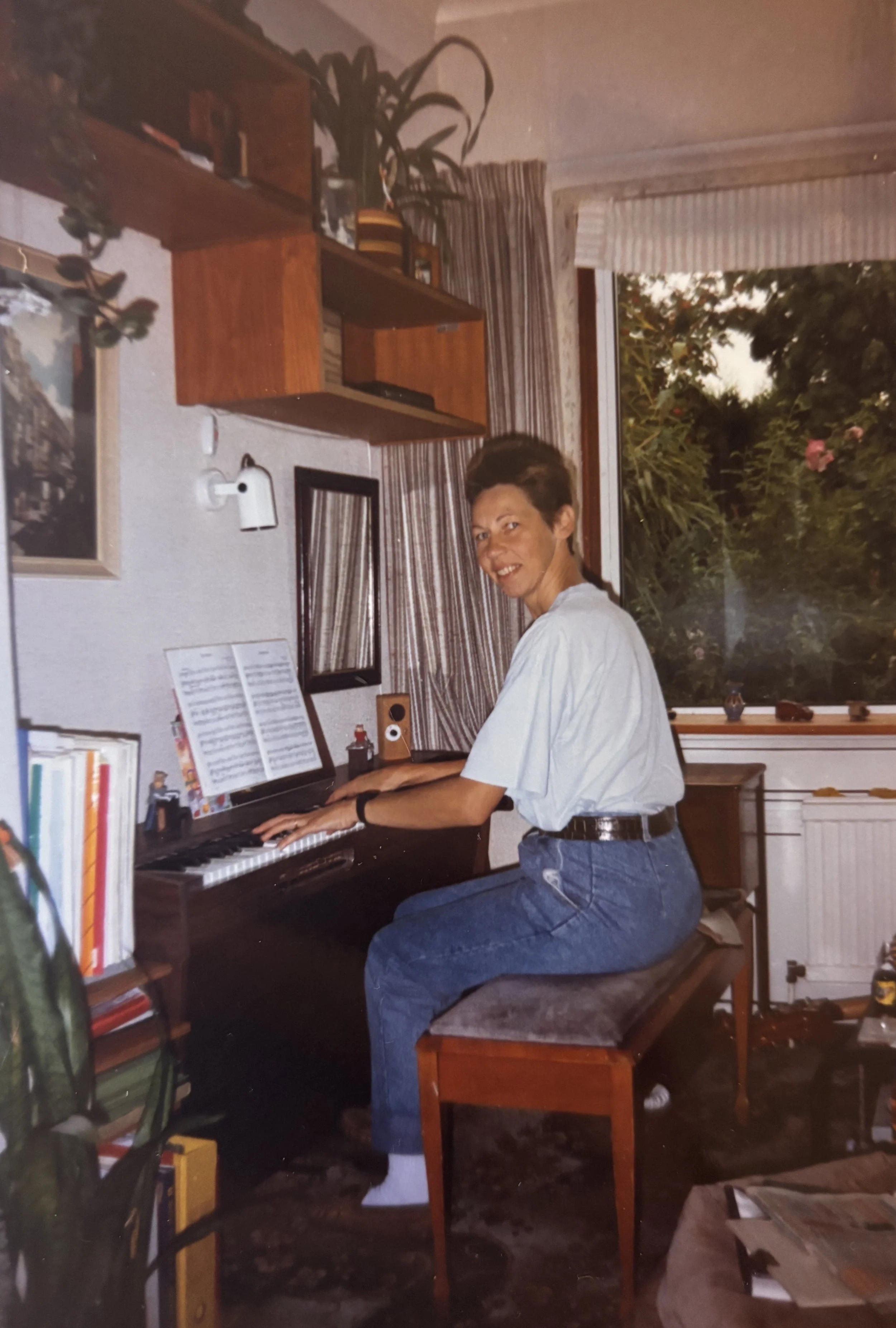

There's one question I've always wanted to ask her. So when she plays piano for me and my sister, she's amazing. She practices every day and she's basically note perfect. But for some reason she's always really nervous before she plays, and I don't know why. So I ask her.

Paula Croxson shares her story at QED Astoria in Queens, NY in May 2025. Photo by Zhen Qin.

I say, “Mom, you know you’re so amazing as a piano player. Why are you always so nervous when you’re playing?”

She said, “Well, I have a story for you.” And she tells me about how, when she was younger, about my age, she was playing cello and piano all the time. She was studying at the Royal College of Music in London and she wanted to go to university to study music. When she got there, it wasn't quite what she expected. The professor she was hoping to study with had left and was replaced with a professor who studied a thing called 16th century counterpoint, which I didn't really know what that was, but it didn't sound good.

And she felt a little bit out of place there, and she'd already met my dad. She knew that, ultimately, she wanted to settle down and have a family. So she decided that she was going to quit.

Now, one thing to know about university in the UK back then is that it was completely free, but not if you quit. If you quit, you had to pay back the fees that you would have paid because you were a quitter. She didn't just quit, because my mom is really smart, right? She failed on purpose. She failed as perfectly, as note perfectly as her music was so it looked like she failed. She didn't have to pay back the fees.

She failed so perfectly that she felt like she had failed. She felt like a failure for years. She stopped playing music entirely. She buried herself in her family. And she didn't even start again until many, many years later. My dad bought her a guitar as a birthday present and she started to play that. Then, incredibly, taught herself the flute and started teaching lessons, as you do.

So I started to understand her a little bit more, but I also judged her a little bit, because I knew that she had had this amazing gift. Like, who knows what she could have done with that music all those years ago. But she gave it up so she could get married and have kids? so

I never told her this, of course, but I decided for myself that I was not going to give up what I had and I was not going to give up my career for anybody or anything. I was going to be a scientist. That was my thing.

I got into an Ivy League school. And when I finished university, I got into grad school. I remember when I called her to tell her I got into grad school to study neuroscience. She was so proud of me. She was so excited for me. I was so proud of myself for sticking to my guns, getting to grad school, doing what I believed in, becoming a scientist. I was going to make a difference in the world.

In the first year of my PhD, I got another phone call from my mom. She told me she had to have some blood tests. They were testing for a few things just to rule them out. But when she called back, it wasn't good news. She had cancer. AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

This was also 20‑something years ago. There was no immunotherapy, there was no personalized medicine, there was just chemo. So they put her on it as quickly as they could.

I talked with her and I said, “Shall I come home?” I've just started grad school, but I can drop everything and come home. But maybe I shouldn't.

Paula Croxson shares her story at QED Astoria in Queens, NY in May 2025. Photo by Zhen Qin.

And she said, “You won't be able to see me anyway. I'm in a clean room in the hospital. I'm going to be immunocompromised.” And

I realized that I wouldn't be able to give her the one thing that I had. I wouldn't be able to put my arms around her and give her a hug. So we decided I wouldn't come home yet, and I'd see her at Christmas.

I called her every day, I wrote to her, and I carried on in grad school. I really plunged into my studies.

But she didn't make it to Christmas. It was a matter of weeks from the day she was diagnosed to the day she died.

When I went home and I was sitting in the front row at her funeral, I wondered to myself if she had any regrets, because I sure as hell did. I wondered if she regretted giving up the music all those years ago and having that opportunity to do who knows what.

And as I was sitting there just absorbed in my own thoughts, I turned around and I looked behind me in the room. The room was full. It was full of her friends. It was full of her family. It was full of kids now grown that she taught music to and taught swimming to. It was so full, there were people standing at the back of the room. I realized that she had made such a difference every single day. And I knew that there was nothing I wanted more than to be like her.

Thank you.